Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--General Geology

Geography

Topography and Drainage

Morton County is in the High Plains section of the Great Plains physiographic province. It comprises a comparatively flat, nearly featureless plain interrupted by the valleys of Cimarron River and its tributaries and by an extensive area of sand dunes south of Cimarron River. About 60 percent of the area of the county is upland that is predominantly flat, but locally has broad mounds and depressions. More than 30 percent of the area is covered by dune sand, of which about 60 percent has a typical sand-dune topography. In some places the sand dunes form relatively steep, irregular bills, and in other places broad rises and depressions that locally give the area a hummocky topography. Slopes along the stream valleys make up the other 10 percent of the area. These slopes are gentle along parts of North Fork of the Cimarron but are abrupt along the north side of the main channel of the Cimarron.

The highest points in the county are in the northwestern and southwestern parts where the altitude slightly exceeds 3,700 feet. The lowest point is along North Fork of the Cimarron in the northeastern part of the county, and has an altitude of about 3,150 feet. The total relief, therefore, is about 550 feet.

The land surface in Morton County slopes toward the northeast at the rate of about 15 feet to the mile. The slope from south to north in the western part of the county is about 10 feet to the mile and in the eastern part of the county it is about 7 feet to the mile.

Morton County is drained by Cimarron River and its tributaries, all of which are intermittent streams. Cimarron River enters the county from the west at a point about 5.5 miles north of the Kansas-Oklahoma line, flows east-northeast across the county, and enters Stevens County at a point about 10.5 miles south of the Stanton-Morton county line. The valley of Cimarron River is about half a mile wide throughout the county and is 100 to 225 feet deep. It is marked on the north side by rounded bluffs and on the south side by sand dunes. The tributaries of the Cimarron are all north of the river and flow northeastward in a direction roughly parallel to the direction of flow of the Cimarron. The tributary valleys are 50 to 100 feet deep and about one mile wide.

Cimarron River rises in northeastern Colfax county, New Mexico, near the city of Raton, and flows eastward through northern Union County, New Mexico, into Cimarron County, Oklahoma, and across the southeastern corner of Baca County, Colorado, into Kansas. In dry weather it obtains its water from springs and seeps in the Mesozoic and Tertiary rocks that crop out in its drainage basin. Generally there is no visible flow in the Cimarron except after heavy rains, but the water level along much of its course is only a few feet below the stream bed.

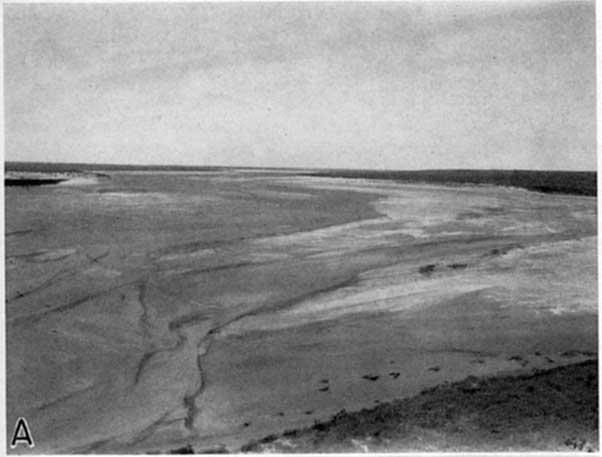

It is interesting to note the great changes that have taken place in Cimarron River and its valley within a comparatively short time. At the present time the Cimarron usually is dry throughout most of its course in Kansas, but it may contain some water in the eastern counties even in dry weather, owing to the addition of water by tributary streams in those counties. In contrast to this, Haworth, in 1897 (p. 21) stated that

In Kansas it [Cimarron River] has water in it throughout the greater part of the year in most of its course.

According to Johnson (1901, p. 664), in 1901 the flow near Arkalon, Seward county, was about 82 second feet and the flow at a point south of Englewood, Clark county, was large enough so that a diversion ditch, using only about one-third of the perennial flow, supplied enough water to irrigate 1,200 acres of bottom land. According to the office of the U. S. Geological Survey in Topeka, the average daily discharge of Cimarron River near Arkalon in 1938-1939 was 42.3 second feet.

In 1911 Parker (pp. 143, 144, 305-311) wrote that--

At irregular intervals the river sinks into the sand and flows beneath the surface for a number of miles. For instance, from the old post office of Metcalf, Okla., to Point of Rocks, Kan., a distance of 25 miles, the channel of the Cimarron is often dry, but at Point of Rocks, Kan., the water comes to the surface at Wagon Bed Springs, a famous camp on the old Santa Fe trail, and the channel is usually full from that point on for a number of miles.

William Easton Hutchison states that the Cimarron River is a constantly running stream throughout the entire width of Morton County, where it has a valley on one side or the other of the channel from one-half mile to three miles in width, on which an abundant crop of natural hay is raised.

Prior to about 1900, the Cimarron River valley was a broad, shallow grass-covered depression, and the water table beneath the valley was near the land surface, but successive floods, particularly that of 1914 have destroyed the grass cover and left a barren area of alluvium between the bluffs on the north side and the sand hills on the south side. The marked change in the appearance of the Cimarron valley from 1899 to 1939 is shown in plate 3.

Plate 3A--Cimarron River valley in 1939 (photo by H.A. Waite).

Plate 3B--Cimarron River valley in Morton County in 1899 (photo by W.D. Johnson).

The area of sand dunes south of Cimarron River has many undrained basins in which rainfall collects, sinks into the porous material, and finds its way to the ground-water reservoir.

Climate

Morton County, like other parts of the High Plains section, has a climate characterized by low precipitation, rapid evaporation, a wide range of temperature variations, hot summers and moderate winters, and occasional blizzards. The winds are strong throughout the year, especially in late winter and early summer, the prevailing winds being from the south and southwest. These strong winds, together with the extended dry periods and overcultivation of the land, have added another feature to the climate of the High Plains--the dust storm.

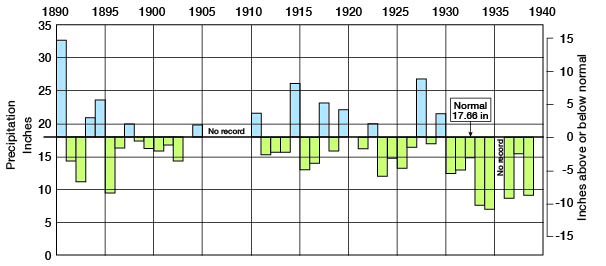

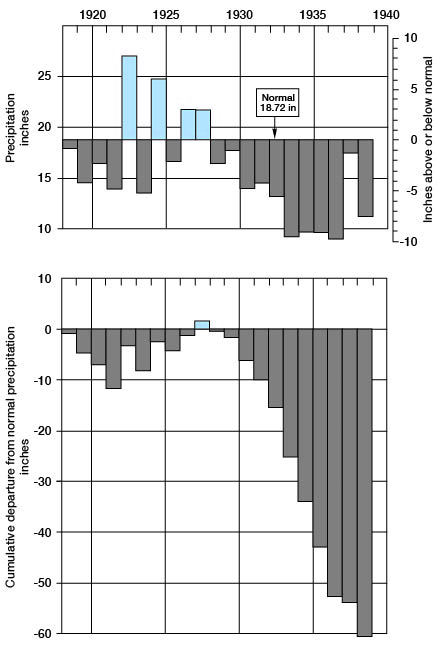

The annual precipitation in the southern High Plains section is extremely variable. According to the U. S. Weather Bureau the greatest annual precipitation on record in Morton County was 32.58 inches in 1891 and the least was 7.09 inches in 1935. (All climatic data, unless otherwise stated, are based on the records of the U. S. Weather Bureau's station at Richfield, Kan.) The mean annual precipitation is 17.86 inches. The graphs show the annual precipitation at Richfield (fig. 3), and the annual precipitation and departure from the normal precipitation at Elkhart (fig. 4).

Figure 3--Graph showing the annual precipitation at Richfield, Kan. (from records of the U.S. Weather Bureau). A larger version of this figure is available.

The data shown in figures 3 and 4 indicate that by the end of 1939 Morton County had experienced the longest period of subnormal precipitation since the weather records were begun. The accumulated deficiency in precipitation at Elkhart by the end of 1939 exceeded 60 inches.

Figure 4--Graphs showing (A) the annual precipitation at Elkhart, Kan., and (B) the cumulative departure from normal precipitation at Elkhart (from records of the U.S. Weather Bureau).

Many of the rains are very localized and torrential. In a single rainstorm in the summer of 1939 more than 4 inches of rain fell on a small area about 5 miles south of Elkhart, while only a trace was recorded at Elkhart. In 1925 the total precipitation recorded at Richfield was 9.8 inches less than that recorded at Elkhart, which is only 20 miles away. July is usually the wettest month of the year and January is generally the driest month. In July, 1895, the precipitation was 12.31 inches, which was more than half of the total precipitation for that year and nearly twice as great as the total precipitation in 1935. The average annual snowfall is 19.9 inches, of which the greater part falls in December and February.

The mean annual temperature in Morton County is 55.3° F. The highest temperature ever recorded in the county was 111° F., in June, and the lowest was -19° F., in January. The average date of the last killing frost in the spring is April 23, but killing frosts have occurred as late as May 22. The first killing frost in the fall has occurred as early as September 23 and as late as November 8, but it generally takes place about October 18. The average length of the growing season is about 178 days; however, the season has ranged from a minimum of 135 days in 1895 to a maximum of 204 days in 1900.

Generally more than 300 days of each year are clear or only partly cloudy, and this high percentage of clear days, together with the high summer temperatures and low humidity, results in a total yearly evaporation of about 60 to 70 inches.

Mineral Resources

Eastern Morton County is a part of the Hugoton gas field, which is potentially one of the largest in the world. The first successful test well for gas was completed on the Boles farm, in sec. 3, T. 35 S., R. 34 W., in the summer of 1920. It had an initial production of 5,000,000 cubic feet a day. Since then more than 35 gas test wells have been drilled in Morton County. Two test wells in the western part of the county were unsuccessful, but all others in the county have had large initial production. The gas is produced from Permian rocks at depths ranging from 2,716 to 3,450 feet.

In the following table are listed the gas test wells drilled in Morton County as of 1938, and the total depth and initial production of each well. Data were supplied principally by the Argus Production Company at Hugoton.

Table 1--Ownership, location, depth, and initial production of natural gas wells in Morton County.

| Owner of Property | Name of company | Location | Depth (feet) | Initial production, cubic feet per day |

| E.M. Watkins | Watkins Land Co. | NE sec. 11 T. 31 S., R 43 W | 1,130 | Dry |

| J.F. Simmons | Texas Interstate Pipeline Co. | SE sec. 16, T. 32 S., R. 39 W | 2,880 | 3,000,000 |

| L.C. Morgan | Argus Production Co. | SE sec. 6, T. 33 S., R. 39 W | 2,775 | 1,000,000 |

| A.O. Mangels | do | SE sec. 4, T. 33 S., R. 39 W | 3,314 | 1,500,000 |

| Hy. Garner | do | SE sec. 18, T. 33 S., R. 39 W | 2,714 | 2,250,000 |

| Wm. Mangels | do | SW sec. 19, T. 33 S., R. 39 W | 2,906 | 1,000,000 |

| E.E. Mangels | do | NE sec. 20, T. 33 S., R. 39 W | 2,704 | 3,250,000 |

| G.L. Hayward | do | NW sec. 31, T. 33 S., R. 39 W | 2,830 | 1,500,000 |

| R.E. Burton | do | SE sec. 11, T. 33 S., R. 40 W | 2,761 | 1,500,000 |

| E.F. Chambers | do | NW sec. 25, T. 33 S., R. 40 W | 2,853 | 1,500,000 |

| Wm. Models | do | NW sec. 4 T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,851 | 13,500,000 |

| R. Armstrong | do | SW sec. 4, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,900 | 11,500,000 |

| Minnie Mangels | do | SW sec. 6, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,900 | 3,750,000 |

| F.A. Thompson | do | SW sec. 7, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,900 | 3,000,000 |

| G.L. Hayward | do | NW sec. 8, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,852 | 4,500,000 |

| S.M. Dreibelbis | do | NW sec. 9 T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,810 | 13,000,000 |

| S.M. Dreibelbis | do | NE sec. 9, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,900 | 6,000,000 |

| G.L. Hayward | do | SW sec. 9, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,871 | 14,000,000 |

| L. Snare | do | SE sec. 9, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,800 | 10,000,000 |

| Ralph Armstrong | do | NW sec. 16, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,933 | 8,500,000 |

| F.A. Thompson | do | NW sec. 18, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,810 | 6,500,000 |

| M.S. Dixon | do | SE sec. 18, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,900 | 4,500,000 |

| Geo. Dorth | do | NE sec. 20, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,850 | 6,500,000 |

| L.M. Tillett | do | SW sec. 21, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,840 | 8,500,000 |

| Helen Ehrhard | do | NW sec. 28, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,750 | 9,750,000 |

| W.H. Sullivan | do | NW sec. 29, T. 34 S., R. 39 W | 2,795 | 3,000,000 |

| W.R. Littell | do | SW sec. 24, T. 34 S., R. 40 W | 2,826 | 4,000,000 |

| Mrs. J.W. Watson | do | NE sec. 27, T. 34 S., R. 40 W | 2,716 | 6,000,000 |

| Butts | Hydraulic Oil Co. | Middle sec. 22, T. 34 S., R. 43 W | 3,450 | Dry |

| G.H. Rickarts | Missouri-Kansas Gas Co. | SE sec. 5, T. 35 S., R. 39 W | 2,805 | 6,000,000 |

| Clara L. Greening | Texas Interstate Pipeline Co. | Middle sec. 6, T. 35 S., R. 39 W | 2,000,000 | |

| C.H. Rickarts | do | SE sec. 8, T. 35 S., R. 39 W | 2,854 | 5,500,000 |

| R.S. Phillips | do | SE sec. 9, T. 35S., R. 39 W | 2,838 | 12,000,000 |

| R.S. Phillips | do | SE sec. 16, T. 35S., R. 39 W | 2795 | 10,500,000 |

The initial production of the wells ranges from about 1,000,000 to 14,000,000 cubic feet of gas a day, and the bottom-hole pressure is about 450 pounds to the square inch. Part of the gas is used locally by small communities and by farmers, but most of it is piped to Hugoton where it enters the main pipe lines to Kansas City and Chicago. The ready availability of large quantities of cheap natural gas may be instrumental in the development of the shallow-water irrigation area north of Rolla, which lies within the gas field.

Other than gas, the mineral resources of Morton County are scarce, so far as now known. Gravels along Cimarron River have been used to a very slight extent as road metal and as building stone, but caliche found at many places in the county is used extensively as road metal on state and county highways.

Agriculture

The settlement of Morton County began in the latter part of the 19th century. A great boom in the cattle industry began in 1880, and as a result the entire Great Plains province became fully stocked [The future of the Great Plains: report of the Great Plains Committee, p. 1-112, 1936]. This era was followed by a period of severe drought from about 1886 to 1895, which caused many farmers to abandon the area and forced those who remained to begin breaking the sod to plant wheat. The Homestead Act, which granted only 160 acres of hand to each family, encouraged the growth of wheat farming because 160 acres of land was scarcely sufficient to support a family if they depended entirely upon stock raising. The development of the tractor and other modern farming equipment, together with the unusually high prices that were paid for farm products during World War I, led to overcultivation of the area between 1910 and 1920, and left almost no grazing hand after 1920. The results might have been disastrous had it not been for the period of above-normal precipitation that produced several large wheat crops in the decade between 1920 and 1930.

The largest crop on record was that of 1926, when many fields produced more than 50 bushels to the acre and some yielded nearly 65 bushels. After 1930 there followed a drought worse than any since the county was first settled. For the nine years from 1931 to 1939 the cumulative deficiency of rainfall exceeded 61 inches and the average annual rainfall for that period was nearly 7 inches below normal.

As a result of overcultivation and repeated dry seasons the soil in this area began to be blown, and since 1934 serious damage has been done both by depletion of the soil and by the accumulation of windblown material (pl. 4A).

Plate 4A--Abandoned farm west of Richfield, showing accumulation of wind-blown dust around the barn (photo by S.W. Lohman).

The soils of Morton County are predominantly of three types (soil types 1, 2, and 5 of Joel, 1937, pp. 8-14): Soil type 1 is a heavy, compact, dark soil consisting of clay loams and silty clay loams and is especially suited for growing wheat and other small grains. This type of soil is derived from the loess that covers the northern half of Morton County (pl. 1). Although this type of soil is very susceptible to wind erosion, it is very thick and is not easily depleted.

Soil type 2 is a moderately friable brown and light-colored soil consisting of silt loams and clay loams over a calcareous subsoil. This type of soil is derived from the Ogallala formation and possibly in part from a very thin blanket of loess.

Soil type 5 is a light-textured, sandy soil made up of sands and loamy sands. It is derived from old subdued sand dunes and is subject to severe wind erosion where cultivation has removed the vegetative cover. These soils are very favorable for the cultivation of row crops, especially sorghums.

Because of the predominance of soils that are susceptible to severe wind erosion, Morton County has been more seriously damaged by the wind than has any other county in the entire "dust-bowl" area. More than 78 percent of the county is affected by serious wind erosion (Joel, 1937, p. 44). In much of this area, however, the wind erosion is being checked, in part by the work of the Soil Conservation Service.

In 1935, a total of 339,818 acres of land was under cultivation in Morton County (Joel, 1937, pp. 16-21). There were 475 farms and the average farm comprised 715 acres. About 45 percent of these farms were operated by tenants and about 55 percent were operated by time landowners or their employees. In general about 30 to 50 percent of the crop is abandoned each year before harvest, according to the county farm agent. Much of the badly eroded land is being purchased by tile Soil Conservation Service. By May 1, 1940, a total of 90,651 acres had been bought and 15,000 acres more was under option, according to Soil Conservation Service figures.

Wheat is the predominant crop in Morton County, as in other parts of southwestern Kansas. The wheat acreage increased from 19,999 acres in 1924 to 71,852 acres in 1930. The following list of crops grown in Morton County was compiled by the 1930 census.

Table 2--Acreage of principal crops grown in Morton County in 1930.

| Wheat | 71,852 |

| Sorghums | 34,321 |

| Corn | 18,334 |

| Broomcorn | 10,786 |

| Barley | 4,461 |

| Others | 402 |

Population

According to the Census Bureau the population of Morton County in 1940 was 2,186, or about 3 persons to the square mile. This is about a 46 percent reduction in population during the decade.

The principal cities are Elkhart, Rolla, and Richfield. Richfield, the oldest city in the county, once had a population of about 1,500, but now has only 96 residents. Elkhart was organized after the building of the railroad through the county in 1912. Its population in 1930 was 1,435, but in 1940 it was only 902. Rolla, incorporated in 1921, had a population of 437 in 1930, but in 1940 it had only 284 inhabitants.

The fluctuations of the population in Morton County have been closely related to the fluctuations of climatic conditions and crop prices. The population of the county was 724 in 1890, but decreased to 304 in 1900, after the severe drought between 1886 and 1895. The development of the tractor and the rising war-time prices caused the population to increase rapidly to 3,177 by 1920. The population of the county continued to increase during the next decade because of a series of good crop years, but since 1930 it has decreased considerably as a result of the dust storms and drought.

Transportation

A branch line of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway was built through the county in 1912. It extends from Dodge City, Kan., to Boise City, Okla., and serves the cities of Elkhart, Wilburton, and Rolla.

One hard-surfaced road, Kansas highway 45, crosses the county parallel to the railroad from Rolla to Elkhart. Kansas highway 27 is hard surfaced from Elkhart to Cimarron River and is topped with caliche from the river to Richfield and to Johnson. A caliche-surfaced road, Kansas highway 51, extends from the Colorado-Kansas boundary through Richfield, Rolla, and Hugoton.

The hard-surfaced roads are the only all-weather roads in the county. Because of the slight precipitation and great evaporation, however, the earth roads are passable during most of the year. Drifting sand in the area south of the river makes the roads impassable more often than do rain and snow. Very few roads have been built across the sand dunes south of the river.

Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--General Geology

Kansas Geological Survey, Morton County Geohydrology

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

Web version Sept. 2004. Original publication date March 1942.

URL=http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/Geology/Morton/04_geog.html