News Release, Kansas Geological Survey, Nov. 27, 2018

LAWRENCE—After an upsurge in earthquakes was attributed to nearby underground disposal of wastewater during a south-central Kansas oil boom, wastewater injection was scaled back and the seismicity subsided. Then, unexpectedly, earthquake activity picked up farther afield.

New research by the Kansas Geological Survey at the University of Kansas explains how that happened and why, over time, wastewater disposal can cause earthquakes at a much greater distance from the point of injection than previously thought.

Although it is unprecedented to suggest injection practices could contribute to fault slippage 55 miles away, as the KGS study does, the amount of fluid injected—along both sides of the Kansas-Oklahoma state line—was also unprecedented.

Saltwater produced with oil and gas is commonly injected back underground into deep rock layers. In Kansas, most of it goes into the Arbuckle Group, a thick formation made up of porous limestone and other sedimentary rocks. The Arbuckle readily takes in and confines the water, but high injection rates sustained over time can drastically increases pressure in fluid-filled rock pores, and that pressure can spread.

"Wastewater injection increases pore pressure within an injection interval such as the Arbuckle Group, but it can also increase pore pressure in any rocks that are hydraulically connected to it," said Shelby Peterie, KGS research geophysicist and lead author of an article in the geophysical publication EOS that outlines the KGS's findings.

The spread and effect of pore pressure, however, is difficult to predict.

"Although pressure change may be large enough to trigger earthquakes on critically stressed faults near a high-volume injection well a short time after injection begins, it may take months to years for increased fluid pressure to travel large distances," Peterie said.

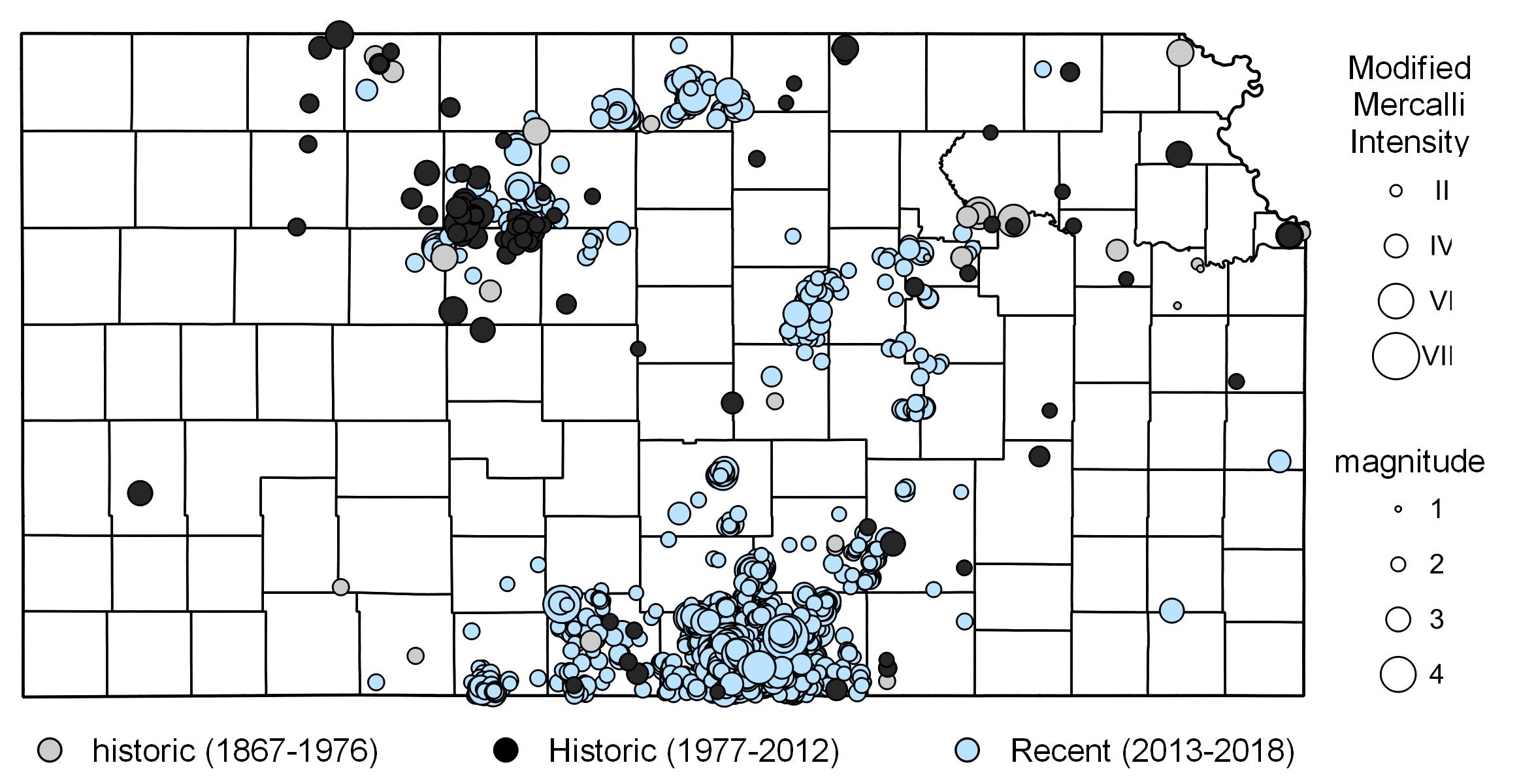

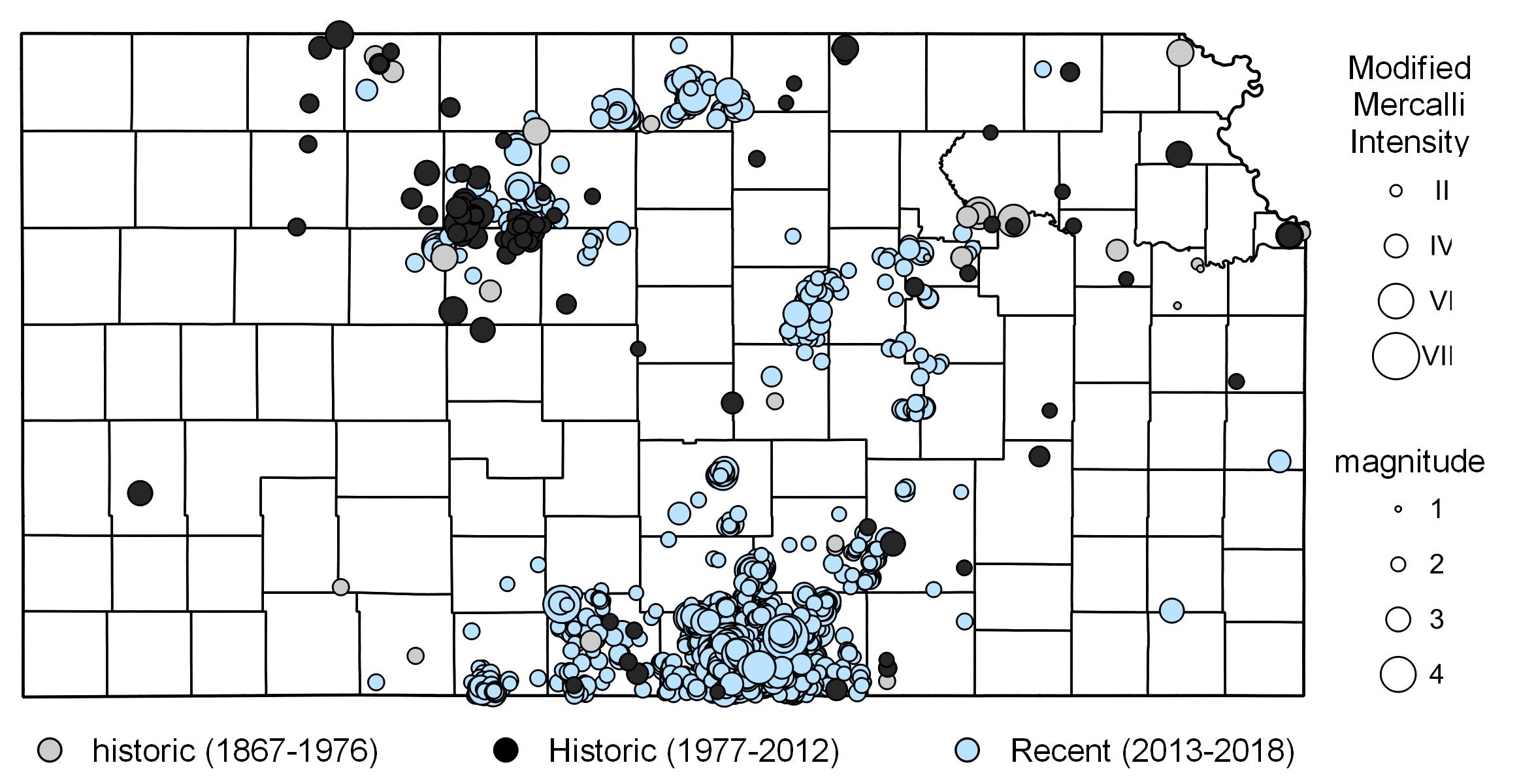

The initial seismic upswing in Kansas started in 2013 within a few miles of the wastewater disposal wells, mainly in Barber, Harper, and Sumner counties. The unforeseen influx of earthquake activity farther north around Hutchinson started in 2017.

"As epicenters recorded by the KGS earthquake monitoring network progressed north from injection sites near the Oklahoma border to Kingman and Reno counties, it seemed likely they were following a pressure perturbation from the south," Peterie said.

Because injection rates in disposal wells outside the southern tier of counties remained fairly constant, they were ruled out as a major contributor to the seismic uptick to the north. Instead, the KGS researchers surmised, the cumulative effects of the high-volume injection along the state line caused earthquakes to migrate dozens of miles away from the disposal wells.

To test that hypothesis, they looked at fluid-pressure measurements taken at the bottom of wells that reached into the Arbuckle and were up to 55 miles away from the high-volume injection wells. Those pressures, they found, had increased in recent years more than expected based solely on nearby injection operations.

The fluid-pressure measurements were reported for Class I wells used for industrial-waste injection, not oil-field disposal wells. Operators of wells for disposal of wastewater from oil and gas operations, or Class II wells, also drill largely into the Arbuckle, but they are not required to report bottom-hole fluid pressures.

Because fluid-pressure data from the Arbuckle are available, the KGS had a unique opportunity to study the widespread effects of wastewater injection.

"In many other places, bottom-hole pressure is not routinely monitored," Peterie said. "In Kansas, regional monitoring of Arbuckle Group fluid pressure has provided us with strong evidence of pressure diffusion away from the high-volume injection wells in south-central Kansas."

Initially, operators of the newly completed Class II disposal wells in south-central Kansas were permitted to inject fluid into the ground at rates three to four times historic levels. By 2015, an unparalleled amount was being injected into an area about the size of two counties spanning both sides of the Kansas-Oklahoma state line.

Following a Kansas Corporation Commission order to reduced injection volumes in the area, the number of earthquakes of magnitude 2 or greater in the injection-restricted footprint dropped from nearly 800 in 2015 to 250 in 2016. In contrast, the number of magnitude 2 or greater earthquakes in Reno County rose from five in 2016 to 30 in 2017. In the first ten months of 2018 there were 34.

Most earthquakes in Kansas, natural or induced, are too small to be felt, although slippage along a fault of sufficient length and under the right stress conditions can trigger an earthquake large enough to cause damage. Located in a tectonically stable region, the state is at low risk for damaging earthquakes.