Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Summary of Stratigraphy

Geography

Topography and Drainage

Ford County is situated in the Great Plains physiographic province, much of the county falling within the subdivision known as the Plains Border section (Fenneman, 1930). About 75 percent of the county consists of upland plains and the remainder of stream flood plains and intermediate slopes. South of the Arkansas River the upland plain slopes southeastward from altitudes of about 2,720 feet along the western boundary at a point about 10 miles north of the southwestern corner of the county to about 2,390 feet along the eastern boundary on the upland plains about 4 miles east of Bucklin. North of Arkansas River the upland plain descends from an altitude of about 2,660 feet along the western boundary at a point about 2 miles north of Arkansas River to about 2,280 feet along the eastern boundary at a point about 2 miles south of the northeastern corner of the county. The undissected surfaces of the uplands in general are comparatively flat and featureless, but locally the surface is undulating and is characterized by broad gentle swells and shallow depressions.

The Arkansas River valley ranges in width from about 2 miles along the western border to about. 4 miles along the eastern border, and is 50 to 160 feet deep. The valley is bordered by moderately steep slopes or bluffs on the north side of the river and by a wide zone of sand hills on the south side (pl. 1).

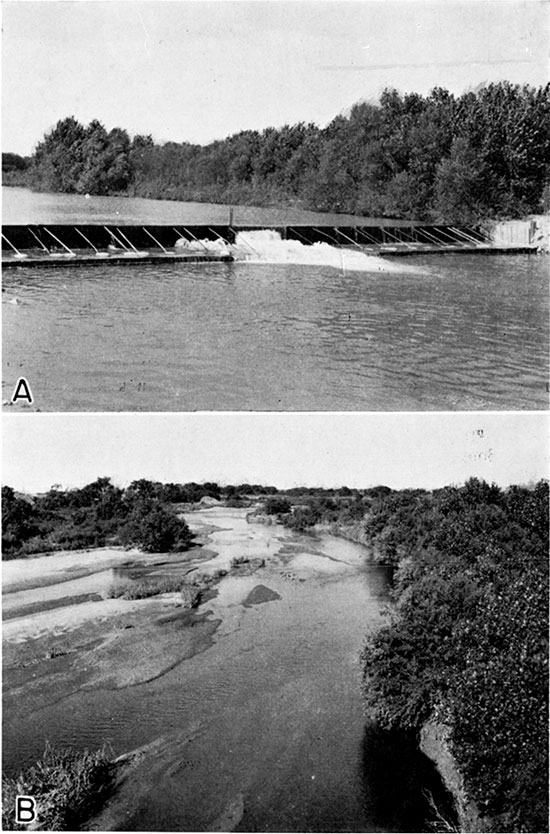

The county is drained by Arkansas River which enters the county along the western boundary at a point about 2 miles northeast of Howell and flows in a southeasterly direction to a point east of Ford, where it turns and flows northeastward, leaving the county near the middle of the eastern boundary. The change in course near Ford is part of a large and unusual bend that the river makes in passing from eastern Ford County northeastward to Great Bend, where it again changes direction and swings southeastward. During the summer months Arkansas River often dwindles to an insignificant stream or disappears almost entirely in its sandy bed with little or no visible flow. At such times the sandy stream bed is threaded by shallow channels, as shown in plate 4B. During periods of flood the stream flow is increased in volume, which results in a general overflow of the stream banks and the inundation of the adjacent floodplain. The average gradient of Arkansas River in Ford County is about 7 feet to the mile. Of the several tributary streams to Arkansas River, only Mulberry Creek on the south joins the main stream within the county.

Plate 4--A, Dam across Arkansas river. Diverts water for the Wilroads Gardens rehabilitation project. Located about 3 1/2 miles below Dodge City in the SW SE sec. 4, T. 27 S., R. 24 W. B, Typical view of Arkansas river. Looking downstream from the Bucklin bridge about 7 miles north of Bucklin.

North of the river, where the surface slopes to the northeast, the northeastern drainage heads within a mile and a half of Arkansas River in some places (pl. 1). The largest tributary stream north of the river in Ford County is Sawlog Creek, which rises in the northwestern corner of the county, flows eastward along the northern edge of the county, and leaves the county at a point about 3 1/2 miles east of U.S. Highway 283. Sawlog Creek joins Buckner Creek at Hanston in eastern Hodgeman County. Duck Creek, which heads about a mile north of Dodge City, flows northeast and enters Sawlog Creek at a point about 2 1/2 miles west of U.S. Highway 283. Five-mile Creek heads about 2 miles west of Wright and flows northeast to join Sawlog Creek at a point about a mile east of U.S. Highway 283. Spring Creek heads about 2 1/2 miles northeast of Wright, flows northward and joins Sawlog Creek about 2 miles east of U.S. Highway 283. A large area southeast of Spearville is drained by Coon Creek and its chief tributary, Cow Creek. Coon Creek heads about 3 miles southwest of Spearville and roughly parallels Arkansas River, leaving the county at a point about 7 miles south of the northeastern corner. With the exception of Duck Creek, which is largely spring fed, most of the tributaries are usually dry.

South of Arkansas River Mulberry Creek is the principal tributary. An area in the southeastern corner of the county in the vicinity of Bucklin is drained by Rattlesnake Creek, which flows northeastward and joins Arkansas River southwest of Alden in Rice County. It is an intermittent stream and is dry most of the year. Crooked Creek enters the southwestern corner of the county at a point, about 1 1/2 miles east of the southwestern corner, makes a broad loop, and swings out of the county at a point on the south county line about 1 3/4 miles east of its point of entry. Throughout its course in Ford County Crooked Creek has eroded a channel of sufficient depth to intercept ground water from springs and seeps, with the result that the creek bed seldom is entirely dry, although actual flow may at times be supplanted by scattered pools along the stream bed. The anomalous features of the reversal in the direction of flow of this stream are discussed under a later section.

Mulberry Creek heads just to the west in Gray county and enters Ford County at a point about 11 1/2 miles north of the southwest corner, flows southeastward to a point about 5 miles northeast of Bloom, after which it swings northeastward to join Arkansas River about 1 mile east of Ford. This stream is usually dry in its upper reaches and throughout much of its course, but carries a small amount of water the year round in a short stretch above its mouth.

The tributary streams north of the Arkansas River, with the exception of Coon Creek, have cut their channels from 100 to 150 feet below the level of the uplands and in general have narrow flood plains bordered in some places by rather precipitous bluffs. The northern part of the county comprises a deeply dissected area in which encroaching streams such as Sawlog, Duck, and Five-mile creeks are gradually destroying the original plains surface and have cut through the Ogallala formation into the underlying Cretaceous rocks. South of the river the amount of dissection is not as great and tributary streams have not cut their channels into bedrock. Resistant caliche beds, so characteristic of the plains surface north of the river, generally are absent south of the river, and the tributary streams have eroded valleys lacking in precipitous bluffs but with numerous closely-spaced gullies entering from both sides. Mulberry Creek has cut below the plains surface to depths of 80 to 120 feet, but, unlike the streams north of the river, the intermediate slopes on both sides of the valley are gentle. The gullies tributary to Rattlesnake Creek in the southeastern part of the county give rise to a semi-badland type of topography. Near the southwestern corner of the county the plains surface slopes toward the Crooked Creek valley and comprises the northern part of the Meade artesian basin. Within Ford County the channel of Crooked Creek has been incised only to a depth of about 10 feet below its floodplain and has not yet reached base-level.

Population

According to the census of 1940, Ford County had a population of 17,254 and an average density of population of 15.9 inhabitants to the square mile, as compared with 21.9 for the entire state. The population in 1930 was 20,647, indicating a reduction of 3,393 during the decade. Dodge City, the county seat, had a population of 8,487 in 1940, having decreased from a population of 10,059 in 1930. Bucklin had a population of 832 in 1940, Spearville, 603, and Ford, 296. Population figures are not available for Fort Dodge (location of the Kansas Soldiers' Home), Wright, Bellefont, Bloom, or Kingsdown.

Transportation

Ford County is served by the main lines of two railroads as well as a branch line of each. The main line of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway traverses the county from cast to west, following the north side of the Arkansas River from Dodge City westward. The main line of the Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad from Chicago to Tucumcari, New Mexico, crosses the southeastern part of the county. A branch line of the Santa Fe crosses the river at Dodge City and goes southwestward to Boise City, Oklahoma. A branch line of the Rock Island crosses the river at Dodge City and joins the main line at Bucklin, paralleling the river as far east as Ford.

U.S. Highway 50 South (paved) parallels the Santa Fe Railway for most of its route across the county, a slight deviation being made at Wright, where the highway continues straight west for 6 miles and thence south into Dodge City. U.S. Highway 154 (paved) enters the county 8 miles north of the southeast corner and continues west for 7 miles, turns northwest to Ford, whence it follows the north side of the river to Dodge City. U.S. Highway 54 parallels the main line of the Rock Island, passing through Bucklin, Kingsdown, and Bloom. State Highway 34 (oil-surfaced) enters the county 5 miles south of Bucklin, continues north through Bucklin, and joins U.S. Highway 154 two and one-half miles northwest of Bucklin. State Highway 45 (oil-surfaced) starts at Dodge City and parallels the Elkhart branch of the Santa Fe, leaving the county about 13 miles north of the southwest corner. U.S. Highway 283 (oil-surfaced) traverses the county from north to south through Dodge City.

Ford County has a well-planned and coordinated system of improved farm-to-market roads. Many of the county roads are graveled and are kept in good condition throughout the year, and many of the section roads have been graded. In general, little or no difficulty in encountered in traveling anywhere within the county.

Agriculture

Agriculture is the chief occupation in Ford County. Dodge City serves as a distributing center and trading point for much of southwestern Kansas. Wheat farming, some cattle raising, and general farming are the principal types of agriculture prevailing in the county. In the Arkansas valley the principal crops consist of wheat and other grains, grain sorghums, several kinds of stock feed, corn, alfalfa, sugar beets, potatoes, and garden truck of all kinds. Irrigation is practiced in the Arkansas valley and in some of the smaller stream valleys, and there are a few irrigation wells on the uplands. In 1938, 3,200 acres were under irrigation in Ford County (see section on Irrigation supplies).

Cattle raising was the principal industry in Ford County when settlement began. With the penetration of railroads into western Kansas after 1860, Dodge City became a famous frontier town--the center of important lines of freighting and the headquarters of the cattle business. This industry attained its maximum development in 1884 when herds aggregating 800,000 cattle tended by 3,000 men passed through Dodge City from Texas on the way north. Overgrazing became a problem during the eighties, the seriousness of which increased as the carrying capacity of the range decreased. Cattlemen suffered great losses as a result of the unusually severe winter of 1886-'87 when great numbers of cattle perished. The prolonged drought that followed (1886-'95) brought further losses and homestead settlement contributed to the difficulties. Thus large-scale cattle ranching was gradually replaced by smaller operations under individual ownership. Years of relatively abundant rainfall from 1910 to 1917, together with high wheat prices brought about by European demand following the outbreak of the World War, gave impetus to the raising of wheat and offered the wheat farmer tangible inducements to produce it in great quantities. Other factors stimulated the process of plowing up the prairies almost to the present time, chief among which were progress in methods of dry farming, and, finally, the introduction of power machinery. With the coming of the tractor and the combine more acres could be seeded because more could be harvested. The common practice was to plow and seed as much land as possible, and then hope for adequate rain, a big crop, and a satisfactory price. Wheat acreages expanded until in 1929 approximately 334,000 acres were harvested. With the coming of several consecutive years of low rainfall associated with the drought of 1931-'39, grain yields were greatly reduced and farm incomes were lessened accordingly. The average harvested acreage of wheat from 1930 to 1934 was reduced to 236,000 acres a year. Many of the wheat growers who had formerly maintained small herds of cattle were forced to sell all or a part of them because of lack of pasturage and forage. For a more detailed historic discussion of the settlement and land use of the High plains the reader is referred to a report entitled "The Future of the Great Plains" (Great Plains Committee, 1936).

Ford County has a total area of 693,120 acres. According to the census of 1940, about 51 percent of the land in use in 1939 was devoted to crops and about 49 percent to grazing. In 1940 one percent of the farms were less than 100 acres in size, 6 percent of the farms ranged in size from 100 to 259 acres, 26 percent ranged from 260 to 499 acres, 43 percent ranged from 500 to 999 acres, 24 percent were 1,000 acres or larger. On April 1, 1940, Ford County had 1,485 farms with an average area of 479.4 acres each. The pastures of Ford County are of the short-grass type and consist chiefly of buffalo grass. In 1939, of the total farm land, 28 percent produced no crop, 24 percent was classified as idle or fallow land, 20 percent was devoted to winter wheat, 16 percent was classified as wasteland and included woodland, house yards, barn yards, feed lots, lanes and roads, 8 percent was classified as plowable pasture, 3 percent as sorghums, including sorghums cut for hay and pasture, and less than 1 percent was devoted to barley, oats, hay, sugar beets and miscellaneous crops.

With the exception of relatively small areas in the extreme northern and northeastern parts of the county, where the soils have been formed from the weathering of the Greenhorn limestone, the soils of Ford County have been formed from the weathering of the underlying plains surface. Throckmorton and others (1937, pp. 69-71) describe these soils as follows:

"These soils are dark gray to brown in color, friable, deep, and relatively easily cultivated. The subsoils are deep and consist of yellowish-brown to grayish-brown silty clay barns and clay learns. The subsoils are sufficiently friable to permit deep penetration of moisture and plant roots. Sheet erosion has taken place on the more sloping soils and in some localities has practically removed the surface layer of soil. Practically all of the soils in the county under cultivation are subject to erosion by wind, but in most cases this can be prevented relatively easily by the adoption of good methods of soil management."

With sufficient moisture the soils are capable of producing large yields. The soils on the upland are suitable for the raising of wheat and grain sorghums. The bottom-land soils are capable of producing these crops and also alfalfa, sugar beets, potatoes, and various garden truck.

Natural resources and industries

Sand and gravel deposits are the chief mineral resource in Ford County. These deposits are abundant along Arkansas River, both in the present stream bed and in low terraces near the margin of the present flood plain, and they are excavated extensively by shovels or by centrifugal pumps at many different points. Sand and gravel deposits are also worked in the northern part of the county in terrace deposits along Sawlog Creek and several of its tributaries, notably in sections 7 and 17, T. 25 S., R. 23 W. The locations of the more important gravel pits are shown in plate 1. The chief use of sand anti gravel is for road surfacing, but smaller amounts are used in concrete aggregate for paving, buildings, road culverts, and bridges.

Building stone is quarried at several places in the northern part of the county. The Greenhorn limestone is the most commonly used stone in the county, although the Dakota formation has been quarried rather extensively in the past. The limestone is used for buildings and other structural work and for road metal. Some of the harder calcareous beds in the Ogallala formation have been quarried for road metal in the SW 1/4 sec. 28, T. 27 S., R. 22 W.

There is no commercial production of oil or gas in Ford County, although several tests have been drilled. Gas was reported in one test drilled in the SW 1/4 NE 1/4 sec. 34, T. 27 S., R. 21 W.

In 1936 samples of rock were collected from exposures of the Ogallala formation and Greenhorn limestone along Duck and Saw-log creeks northeast of Dodge City, and tests were made to determine their suitability for making rock wool (Plummer, 1937, pp. 59-64). Extremely fine white rock wool was made from the samples of "mortar beds" of the Ogallala.

Samples of Cretaceous clays in the Dakota formation in the northern part of Ford County were collected in 1940 by Plummer and Romary in connection with an extensive study of the ceramic possibilities of Kansas clays. The results of the tests on the samples from Ford County are to be published as a bulletin of the Kansas Geological Survey.

Climate

(Following three paragraphs from Anonymous, 1930.)

Ford County is characterized by a rather dry climate, abundant sunshine, warm summer days that are alleviated by a good wind movement and low relative humidity.... Hot winds occasionally blow during a dry, heated period and are the cause of great crop damage and much discomfort while they are occurring.

Winter months, as a rule, are slightly colder and windier than in eastern Kansas, but are drier. Snowfall, however, is usually light, seldom totaling more than 20 inches in the course of a winter season, and it is rare that the ground is covered for more than a week at a time. It usually falls with a high wind and lies very unevenly on the ground.

The moisture that falls as rain and snow from season to season is the chief limiting factor of crop growth. The distribution of precipitation through the year is peculiarly favorable for crop growth. Approximately 77 percent of the annual amount falls in the six months, April to September, inclusive, when the growing season is at its height and moisture is most needed. The driest month is generally January, after which there is a steady increase in the average monthly totals that mounts rapidly in April and continues until July. A sharp decrease in the average rainfall begins the latter part of October or the first part of November and continues into the winter. Precipitation in this part of the state is inclined to be irregular in occurrence. (Anonymous, 1930.)

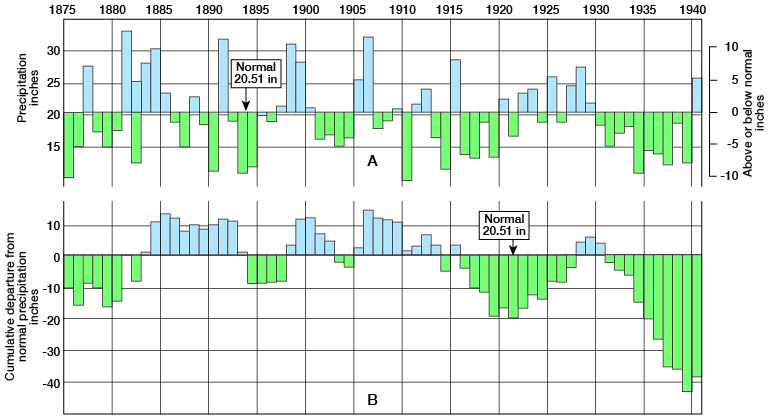

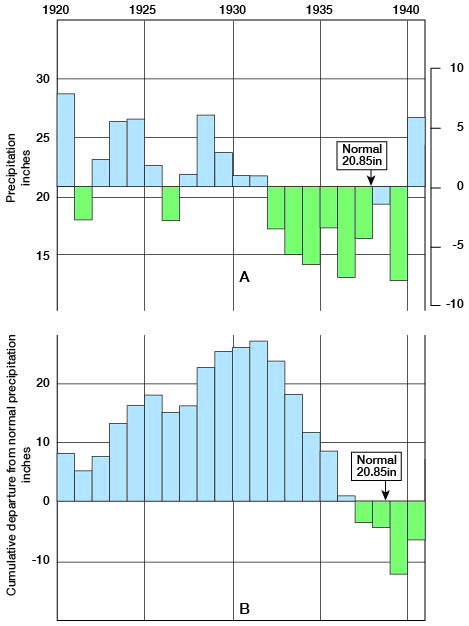

According to the U.S. Weather Bureau the normal annual precipitation at Dodge City is 20.51 inches, and at Bucklin it is 20.85 inches.

The annual precipitation and the cumulative departures from normal precipitation for each of these stations are shown in figures 3 and 4. The precipitation at Dodge City has averaged 4.85 inches below normal for the last 10 years, 1930-1939, inclusive. This is by far the longest consecutive period of subnormal precipitation in the 65-year record of the station. The longest periods of subnormal precipitation previously were only of 4 years duration and began with the years 1901 and 1916. The deficiency in annual precipitation of 9.51 inches in 1934 was exceeded previously three times; in 1875 the deficiency was 9.83 inches and in 1893 and 1910 it was 10.39 inches. By the end of 1939 the cumulative departure from normal precipitation amounted to about 42 1/2 inches--an amount equal to more than twice the normal annual precipitation.

Figure 3--Graphs showing (A) the annual precipitation at Dodge City, Kansas, and (B) the cumulative departure from normal precipitation at Dodge City.

The driest years since the beginning of record at Dodge City were 1893 and 1910. The wettest year was 1881 when a total of 33.55 inches was recorded. Other unusually wet years were: 1891, with a total of 32.34 inches; 1898, 31.46 inches; 1906, 32.54 inches; and 1915, 28.75 inches.

The period of record at Bucklin is much shorter than that at Dodge City. As shown in figure 4, the precipitation at Bucklin was above normal during the period 1920-1931, but subnormal precipitation prevailed during the period 1932-1939.

Figure 4--Graphs showing (A) the annual precipitation at Bucklin, Kansas, and (B) the cumulative departure from normal precipitation at Bucklin.

The average annual mean temperature as recorded at Dodge City is 54.3 deg. F. The highest temperature recorded was 109 deg. F. on July 31, 1934, and July 18, 1936, and the lowest was -26 deg. F. in February, 1899. July is usually the warmest month of the year. The coldest month in the year is usually January, although the lowest temperature of record occurred in February. The length of the growing season averages about 189 days, but ranges from 148 to 238 days. (Throckmorton and others, 1937, pp. 69-71.) The first killing frost in the fall occurs generally in September or October, and the last killing frost in the spring occurs generally about the middle of April. Killing frosts have occurred as early as September 23 and as late as May 27.

The prevailing wind direction is from the northwest in January, February, and March; from the southeast during the period April through August; from the south in September; from the southeast in October; and from the northwest in November and December. Generally the windiest months are March, April, and May, and the month of least wind is August. Wind movement is considerably higher in the afternoon than at night. High winds in the early spring often cause much damage by blowing off the loose top soil, especially if it happens to be dry. In such cases soil may be blown from the roots of wheat or the plant may suffer mechanical damage by rapidly moving particles of sand carried by the wind. During several of the severe dust storms in the spring of 1935 all forms of travel, including trains and buses, were stopped in the vicinity of Dodge City and highways were closed.

Prev Page--Introduction || Next Page--Summary of Stratigraphy

Kansas Geological Survey, Ford County Geohydrology

Web version April 2002. Original publication date Dec. 1942.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/Geology/Ford/03_geog.html