Prev Page—Geography || Next Page—Ground Water

Geology

Summary of Stratigraphy

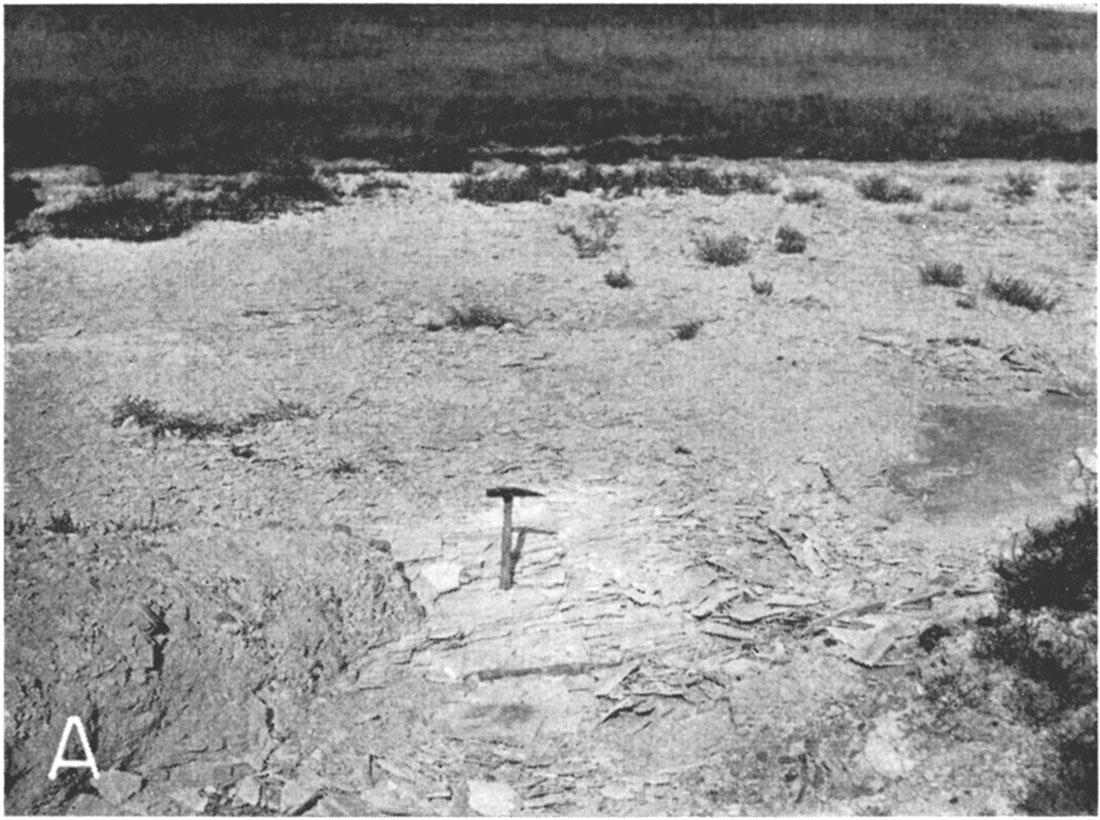

The rocks exposed in Scott County range in age from Upper Cretaceous to Recent. The areal distribution of the formations is shown on Plate 1. The oldest rocks cropping out in the county belong to the Smoky Hill chalk member of the Niobrara formation. This member is best exposed in the northern and northeastern part of the county where streams tributary to Smoky Hill River have cut through the plains surface into the underlying Smoky Hill chalk (Pl. 4B). Other exposures of the Smoky Hill are found also in the sides of several small tributary streams entering Dry Lake from the north and west near the southeastern corner of the county (Pl. 7A). The Pierre shale, which overlies the Niobrara formation in other areas, is absent in Scott County. The Ogallala formation of Tertiary age, which rests unconformably on the Smoky Hill chalk member of the Niobrara formation, is exposed in the sides of many of the stream valleys, but over large areas it is covered by younger deposits of sand and gravel overlain by loess. The undissected plains surface is mantled by deposits of loess ranging in age from Pleistocene to Recent. Dune sand covers an area of approximately 18 square miles near the southeastern corner of the county. A narrow belt of alluvium occupies the valley of Beaver Creek throughout its course in Scott County. The soils, alluvium, drifting dune sand, and terrace deposits are the most recent deposits in the area.

Plate 7A—Thin-bedded Smoky Hill chalk member of the Niobrara formation exposed in SW SE sec. 6, T. 20 S., R. 31 W.

The character and ground-water supply of the geologic formations in Scott County are described briefly in the generalized section given in Table 1 and in more detail in the section on geologic formations and their water-bearing properties.

Geologic History

Parts of the following discussion are taken from a report by Darton (1906, pp. 45-46).

The exposed rocks in Scott County are underlain by older sedimentary rocks of pre-Cambrian age. The stratigraphic sequence of the rocks underlying the surface is fairly well known from the togs and well cuttings of each of the oil tests in the Shallow Water oil pool in south-central Scott County.

Table 1—Generalized section of the geologic formations in Scott County, Kansas.

| System | Series | Formation Member | Thickness (feet) |

Physical character | Water supply | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary | Pleistocene and Recent | Alluvium | 0-20 ± | Gravel, sand, silt and clay comprising stream deposits in Beaver (Ladder) Creek valley. | Yields small supplies of relatively hard water to wells in Beaver (Ladder) Creek valley. | |

| unconformable on older formations | ||||||

| Dune sand | 0-50 ± | Fine to medium sand. Mantles small areas in the southeastern part of the county. Except where reopened by recent blowouts, the dunes are stabilized by vegetation. | Probably does not supply water directly to wells but is important as a favorable catchment area for ground-water recharge to adjacent and underlying formations. | |||

| unconformable on older formations | ||||||

| Loess | 0-30 | Light buff-colored silt containing fine sand and some clay. | Loess deposits occur mostly above the water table and are relatively impermeable. | |||

| unconformable on older formations | ||||||

| Pleistocene | Undifferentiated deposits, including channel deposits along Beaver (Ladder) Creek | 0-200 ± | Predominantly unconsolidated sands and gravels containing silt and clay. Basal channel deposits are cemented in at least one small exposure along Beaver Creek. | Where saturated yield large supplies of moderately hard water to most of the wells in the shallow-water basin. Channel deposits are relatively permeable but generally occur above the water table. | ||

| unconformity | ||||||

| Tertiary | Pliocene | Ogallala formation | 0-160 | Gravel, sand, silt, caliche, and some silty clay. Contains hard and soft layers of sandstone and conglomerate, much of which is crossbedded and cemented with lime. Lower part locally contains mottled bentonitic clay ranging in color from reddish brown to | Yields moderate to large supplies of moderately hard water to domestic and stock wells in many parts of the county. Constitutes the principal source of supply for many of the irrigation wells in Scott Basin. | |

| unconformity | ||||||

| Cretaceous | Gulfian* | Niobrara formation | Smoky Hill chalk | 0-130 ± | Alternative beds of soft chalk and chalky shale. | Yields limited supplies of hard to very hard water to wells in the southeastern quarter of the country. |

| Fort Hays limestone | Massive chalk beds separated by thin, soft, chalky shale. | Not known to yield water to wells in Scott County. | ||||

| Carlile shale | Codell sandstone | 180-230 | Sandstone and sandy shale. | Not known to yield water to wells in Scott County. The Codell sandstone member is reported to yield meager quantities of water to wells in Finney County. The Blue Hill shale and Fairport chalky shale members of the Carlile shale are relatively impermeable | ||

| Blue Hill shale | Bluish-gray clay shale containing septarian concretions in upper part. | |||||

| Fairport chalky shale | Yellow chalky shale with thin limestone beds. | |||||

| Greenhorn limestone | Pfeifer shale, Jetmore chalk, Hartland shale, Lincoln limestone | 0-55 | Alternating beds of chalky shale and thin chalky limestones. | Not known to yield water to wells in Scott County. | ||

| Graneros shale | 25-100 | Dark bluish-gray clay shale containing thin-bedded limestone and sand lenses. | Relatively impermeable; not known to yield water to wells in Scott County. | |||

| Dakota formation | 260-550 ± | Sandstones, shales, and clays. | Not known to yield water to wells in Scott County. The sandstones of the Dakota formation yield moderate supplies of soft water to wells in southeastern Gray County and in Ford County. The Kiowa shale is relatively impermeable. | |||

| Comanchean* | Kiowa shale | Black marine shale and a few thin limestone beds. | ||||

| Cheyenne sandstone | Fine to coarse-grained sandstone and sandy shale. | |||||

| unconformity | ||||||

| Permian | Leonardian and Guadalupian* | Undifferentiated redbeds | 1,150 ± | |||

* Classification of the State Geological Survey of Kansas

Paleozoic Era

Cambrian and Ordovician Periods

Although very little is known of the conditions existing in western Kansas during early Paleozoic time, it is believed that Scott County, along with a large part of west-central United States, was a land surface during early Cambrian time. In the middle part of Cambrian time there began the development of an interior sea with a resultant change to marine conditions. Submergence of the land continued through most of Ordovician time with extensive deposition of lime sediments that were later indurated to form limestones and dolomites. The sandy, cherty dolomite that forms the Arbuckle limestone or "siliceous lime" of Cambrian and Ordovician age was deposited in the earlier part of this interval. In Scott County the Arbuckle is encountered in one well at a depth of about 5,470 feet.

A well in the Shallow Water oil pool penetrates the Viola limestone and Simpson group of Ordovician age. The Viola is a sugary, dolomitic, and very cherty limestone at the top, but becomes finer grained and non-cherty below, grading into the Simpson group at a depth of about 5,450 feet.

Silurian and Devonian Periods

There is little or no evidence that rocks of Silurian and Devonian age are present under Scott County. Either they were never deposited in this area or they were removed by erosion prior to the deposition of the overlying Mississippian strata.

Mississippian and Pennsylvanian Periods

During early Mississippian time there was extensive deposition of marine dolomitic limestone and some shale. According to the logs of oil wells in the Shallow Water pool, Mississippian strata are present under Scott County, the top being encountered at a depth of about 4,650 feet. When production was found initially in the Shallow Water pool it was believed that the producing limestone was of Chesterian (upper Mississippian) age (Ver Wiebe, 1938, p. 138). Norton (1938), however, reports that this oolitic limestone is probably the equivalent of the Ste. Genevieve limestone of middle Mississippian age. In later Mississippian time there was an uplift, during which the surface of the early Mississippian strata was subjected to erosion.

A long period of erosion intervened between the deposition of the youngest Mississippian rocks and the oldest Pennsylvanian rocks. During this interval the limestone of Chesterian age, if deposited originally, may have been removed in Scott County. Alternate subsidence below and emergence above sea level were repeated many times during the Pennsylvanian, giving rise to both marine and continental deposits consisting of sandstone, shale, coal, and limestone. This sequence of deposition was interrupted at times when the land surface was elevated and subjected to erosion. The Pennsylvanian rocks are approximately 1,400 feet thick in Scott County. According to Ver Wiebe (1938, p. 138) the top of the Topeka limestone lies at a depth of 3,600 feet and the top of the Lansing group is approximately 350 feet lower. Below the Lansing-Kansas City-Bronson sequence of limestones are shales and limestones, which may correspond to the Marmaton group and Cherokee shale of eastern Kansas. In Scott County these shales are subordinate to coarse-grained limestones of gray to black color. The composition of the lower Pennsylvanian rocks is somewhat different also, notably in the presence of considerable chert. The basal conglomerate may be represented by red and green shales near the base of the system.

Permian Period

A transitional period intervened in which marine conditions during early Permian time were somewhat comparable to those existing during late Pennsylvanian time, and alternate successions of limestones, dolomites, and shales (Wolfcampian Series) were deposited. Following this there was an interval when beds of continental origin were deposited alternately with beds of marine origin. Gradually continental deposition became the dominant mode of origin for late Permian sediments. Most of the deposition took place in shallow water, so that subsidence must have kept pace with deposition during this interval. It is probable that an arid climate prevailed and evaporation must have taken place in shallow basin, giving rise to extensive deposits of salt and anhydrite interbedded with deposits of gypsum of the Leonardian Series. According to the logs of oil wells in the Shallow Water pool the top of the Permian is encountered at a depth of approximately 1,150 feet. Gypsum of the Blaine formation is encountered at a depth of about 1,430 feet, and anhydrite of the Stone Corral dolomite lies at a depth of about 2,100 feet. Beneath the red beds, the gray shales and anhydrites of the Wellington formation are encountered and these beds continue to a depth of about 2,800 feet where the first dolomite of the Wolfcampian Series appears.

Mesozoic Era

Cretaceous Period

At the close of the Paleozoic, deposition was terminated by an uplift that brought the region above water. This condition probably prevailed throughout most of Triassic time and through Jurassic time, during which there was no deposition and probably considerable erosion. Rocks of Triassic and Jurassic age are not known to occur in Scott County.

As the result of an early Cretaceous uplift there was at first a land surface followed by a shallow-water body in Comanchean time during which the sandstone and shale of the Cheyenne sandstone were deposited. The deposits were laid down either by streams or in a shallow sea or perhaps they were deposited in part on the beach by wind, suggesting that the place of deposition was not far above or far from a shore line (Twenhofel, 1924, pp. 19-21).

Following this there was a change from continental to marine conditions as a result of submergence of the land surface during which time the Kiowa shale was deposited. It is believed that Cheyenne sandstone and Kiowa shale underlie at least a part of Scott County, but in subsurface studies of oil-well samples no attempt has been made to segregate either of the formations from the underlying Dakota. None of the test holes drilled by the State and Federal Geological Surveys in Scott County were drilled deep enough to penetrate strata below the Niobrara formation.

In late Cretaceous time there was a return to conditions similar to those under which the Cheyenne sandstone was deposited and the sandstones, shales, and clays of the Dakota formation were laid down. The Dakota formation is a freshwater deposit that was laid down on beaches and near the shore during an uplift in which the sea retreated far to the south. The top of the Dakota formation is encountered at a depth of about 700 feet in Scott County. The combined thickness of the Dakota formation, the Cheyenne sandstone, and the Kiowa shale in Scott County is approximately 550 feet.

After the Dakota formation was laid down there was a rapid change in the conditions of sedimentation to those under which several thousand feet of shale, lime, and chalk were deposited, beginning with the Graneros shale and including the Greenhorn limestone, the Carlile shale, the Niobrara formation, and the Pierre shale. This marks the beginning of very extensive later Cretaceous submergence, in which marine conditions prevailed over a large area for a long time. Sedimentation was interrupted from time to time by emergence of the land to a point at or near sea level. According to the logs of oil wells in the Shallow Water pool, the base of the Niobrara formation is encountered at a depth of about 310 feet, and the top of the Greenhorn limestone is found at about 540 feet, indicating a thickness of about 230 feet for the Carlile shale.

Cenozoic Era

Tertiary Period

Prior to the deposition of Tertiary sediments there was a period of folding during which the major features of the bedrock depression in Scott and Finney counties may have been formed. A broad asymmetrical trough, with its axis extending from Garden City to Scott City and northward, was developed. At the beginning of Tertiary time an extensive land surface existed in western Kansas; this surface was subjected to erosion largely effected by through-flowing streams. During this interval great thicknesses of Upper Cretaceous sediments were removed, so that in Scott County all Cretaceous strata above the Niobrara are missing and variable thicknesses of the upper part of the Niobrara have been removed. The present shape of the trough in cross section is shown by sections A-A', B-B', and C-C' in Figure 5, and the approximate configuration of the pre-Tertiary surface possibly modified by post-Tertiary erosion is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 5—A, east-west geologic profile along Kansas Highway 96 through Scott City; B, east-west geologic profile along section road 0.5 mile south of Shallow Water; C, north-south geologic profile across the middle of Scott County.

In late Tertiary time erosion (possibly peneplanation) was followed by an epoch of deposition which started with the accumulation in some parts of the county of beds of plastic greenish and maroon-brown bentonitic clays interbedded with soft grit and sand. This zone may be equivalent to the Woodhouse clays of Wallace County that were described by Elias (1931, pp. 153-158). It is possible that these clays represent a mixture of altered volcanic ash of the Ogallala formation with the clayey products of disintegration of pre-Tertiary beds and that they were deposited under somewhat different conditions. This was followed by an interval during which heavily laden streams from the Rocky Mountains traversed western Kansas and deposited the sediments of the Ogallala formation in a broad alluvial plain.

Some crustal deformation may have taken place after the deposition of the Ogallala, probably along pre-established lines of weakness.

Quaternary Period

Pleistocene Epoch—A period of erosion preceded the beginning of the Pleistocene during which the pre-Pleistocene surface was subjected to subaerial erosion. In early Pleistocene time, streams were rejuvenated as a result of uplift to the west and because of climatic changes, so that erosion followed by sedimentation was resumed. The trough which had been deepened by downwarping or erosion or both was filled with sands and gravels which in turn were mantled by windblown loess. The sand and gravel deposits were laid down by heavily laden streams that probably shifted laterally at frequent intervals. Stream deposition was followed by eolian activity, indicated by the fact that the fluvial deposits grade upward into loess. This seems to indicate that during the latter part of the Pleistocene there was a climatic change with considerable wind movement. Loess deposition has continued intermittently until Recent time.

Recent Epoch—At the beginning of the Recent Epoch, streams began the downcutting that has produced the present topography. It was during this period also that the courses of the several streams were established. The presence of a Cretaceous ridge in eastern Scott County has affected the behavior of streams traversing the county. Beaver Creek or Ladder Creek, a tributary of Smoky Hill River, enters the county from the west and flows eastward to a point about midway across the county from east to west, where it turns abruptly northward, continuing in this direction to its junction with the Smoky Hill. This anomalous change in direction is probably directly related to the structure of the underlying bedrock. Whitewoman Creek is another notable example of a stream whose course has been affected by the position of the underlying bedrock. This stream differs from most other streams in that it has no connection with any other stream, and in times of flood it empties its water into the broad shallow depression at its terminus, known as the Scott Basin.

Terrace deposits of sand and gravel are found in a belt immediately bordering the floodplain of Beaver Creek. Much of the material in the terrace gravels was derived from source areas to the west and was deposited by Beaver Creek at some time during the Pleistocene when it was flowing at a higher level than at present. The terraces are of cut-and-fill origin and probably are of late glacial or post-glacial age.

Dune sand mantles the surface in the southeastern part of the county (Pl. 1). Although its age is not definitely known, it is believed that accumulation of some of the sand started in late Pleistocene time and continued until Recent time. The sand originated possibly from eroded slopes cut in the Ogallala formation and from the Pleistocene sands and gravels. It is possible that the sand was derived either wholly or in part from the strand flats of a lake that formerly occupied the depression now known as Dry Lake. The dune-building winds of the past were in a northerly direction, whereas those of the present time are predominantly southerly. Smith (1940, p. 168) suggested that the presence of a continental ice sheet during one or more of the Pleistocene glacial stages would have provided ready cause for altered wind direction.

Prev Page—Geography || Next Page—Ground Water

Kansas Geological Survey, Geology

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

Web version March 2003. Original publication date July 1947.

URL=http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/Geology/Scott/04_geol.html