Prev Page--Utilization || Next Page--Quality

Ground Water, continued

Utilization of Ground Water, continued

Uses in Agriculture

Irrigation Supplies

Many farmers in the Arkansas valley in Ford County pump water from one or more large wells to irrigate crops--principally feed crops, consisting of sorghums, cane, kafir and sudan. Other crops irrigated from welts included wheat and other small grains, sugar beets, alfalfa, garden truck and miscellaneous crops. In the fall of 1938 an inventory was made of the irrigation wells in Ford County, and estimates were obtained of the total pumpage and number of acres irrigated during 1938. The detailed records of all irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley are given in table 15 and the locations of the wells are shown in plates 2 and 3. Most of the irrigation wells are situated in the Arkansas valley but 10 of them are on the upland south of the valley.

Records were obtained of 187 irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley. The total reported area irrigated from these wells in 1935 was 2,814 acres (table 6), an average of about 17 1/2 acres to the well. Most of the small irrigation wells in the vicinity of Dodge City supply tracts of only 1 to 10 acres and many of the wells are used to irrigate gardens, trees and lawns. Some of the larger wells, of which there are approximately 60, each irrigate more than 100 acres. The water from most of the larger wells is used for irrigating feed crops, and also small grains, alfalfa and sugar beets.

Table 6--Acreage irrigated with water from wells in the Arkansas valley, Ford County, Kansas, in 1938, by townships.

| Township | Number of wells visited |

Number of wells not used in 1938 |

Number of wells not reported |

Acres irrigated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. 26 S., R. 26 W | 12 | 2 | 0 | 490 |

| T. 27 S., R. 26 W | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| T. 26 S., R. 25 W | 95 | 12 | 4 | 859 |

| T. 27 S., R. 25 W | 13 | 1 | 0 | 178 |

| T. 25 S., R. 24 W | 43 | 6 | 0 | 475 |

| T. 27 S., R. 24 W | 4 | 1 | 0 | 175 |

| T. 27 S., R. 23 W | 4 | 0 | 0 | 191 |

| T. 28 S., R. 22 W | 8 | 0 | 0 | 319 |

| T. 26 S., R. 21 W | 5 | 0 | 1 | 95 |

| T. 27 S., R. 21 W | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| T. 26 S., R. 20 W | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Totals | 187 | 22 | 5 | 2,814 |

An estimate of the quantity of water pumped annually from irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley in Ford County, based upon reported estimates of pumpage obtained from well owners, is given by townships in table 7. For wells that are pumped by electricity, pumpage estimates were computed from power records that showed the total number of kilowatt-hours of electricity consumed in 1938.

Table 7--Pumpage from irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley, Ford County, Kansas, in 1938, by townships.

| Township | Number of wells visited |

Number of wells for which pumpage estimates were not available |

Number of wells not used in 1938 |

Pumpage, in acre-feet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. 26 S., R. 26 W. | 12 | 0 | 2 | 956 |

| T. 27 S., R. 26 W. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| T. 26 S., R. 25 W. | 95 | 6 | 13 | 1,614 |

| T. 27 S., R. 26 W. | 13 | 0 | 0 | 196 |

| T. 26 S., R. 24 W. | 43 | 4 | 6 | 1,107 |

| T. 27 S., R. 24 W. | 4 | 0 | 1 | 277 |

| T. 27 S., R. 23 W. | 4 | 0 | 0 | 233 |

| T. 28 S., R. 22 W. | 8 | 1 | 0 | 233 |

| T. 26 S., R. 21 W. | 5 | 0 | 0 | 87 |

| T. 27 S., R. 21 W. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| T. 26 S., R. 20 W. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| Totals | 187 | 11 | 22 | 4,761 |

Mr. Fred Moon, irrigation specialist of the Kansas Power Company, assisted in working out the pumpage estimates based on power consumption. The estimated total quantity of water pumped for irrigation in 1938 was about 4,760 acre-feet.

The total annual pumpage for irrigation in the Arkansas valley varies considerably from year to year, and during any one year varies with the amount of precipitation and with the water requirements of the crops being irrigated. Some wells are not used each year, some standing idle because of the owner's lack of time or facilities, others being out of use because the type of crop did not require irrigation.

Yields of irrigation wells--The yields of irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley in Ford County range from less than 100 gallons a minute up to about 1,200 gallons. Most of the yields of irrigation wells given in table 15 were reported by the owners, but the yields of many irrigation wells in southwestern Kansas, including 15 wells in Ford County, were made in 1938 and 1939 by M.H. Davison and K.D. McCall of the Division of Water Resources, Kansas State Board of Agriculture. Two of the wells in Ford County (522 and 393) were tested in 1938 (Anon., 1938, p. 20) and the others were tested in 1939 (McCall and Davison, 1939, pp. 50-54). The results of these pumping tests are given in table 8.

Table 8--Pumping tests of irrigation wells in Ford County. By M.H. Davison and K.D. McCall of the Division of Water Resources, Kansas State Board of Agriculture, assisted in part by H.A. Waite.

| Well No. in plates 2 and 3, and table 15 |

Discharge (gallons a minute) |

Draw-down (feet) |

Specific capacity (gallons a minute per foot of draw-down) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 180 (a) | 1040 | 5.1 | 204 |

| 181 (b) | 690 | 45.1 | 15.3 |

| 183 (c) | 340 | 18.27 | 18.6 |

| 320 (d) | 1200 | 6.25 | 192 |

| 393 | 765 | 15 | 51 |

| 402 | 320 | (e) 22.9 +/- | 14 |

| 403 | 360 | 22 +/- | 16.4 |

| 417 | 1184 | 15.16 | 78.1 |

| 421 | 983 | 14 | 70.2 |

| 423 | 270 | 20.6 | 13.1 |

| 435 | 765 | 14.3 | 53.5 |

| 485 | 320 | 6.7 | 47.8 |

| 507 | 950 | 19.6 | 48.5 |

| 510 | 690 | 47.8 | 14.4 |

| 522 | 570 | (f) 41.5 | 13.7 |

a. Ten shallow and two deep wells connected to same pump; one deep well shut off during test; draw-down given represents average for the 10 shallow wells only--draw-down in two deep wells not known.

b. Well taps both the shallow water in the alluvium and the deeper water in the underlying Ogallala formation.

c. One shallow well and one deep well connected to same pump.

d. Five shallow wells connected to one pump. Draw-down given is average for all five wells.

e. Actual draw-down greater than the figure given, because water levels below certain point could not be measured.

f. Estimated.

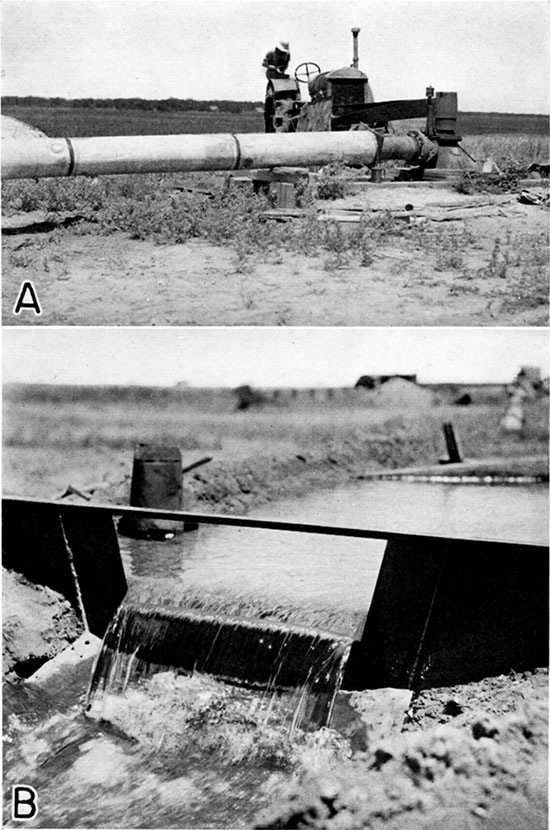

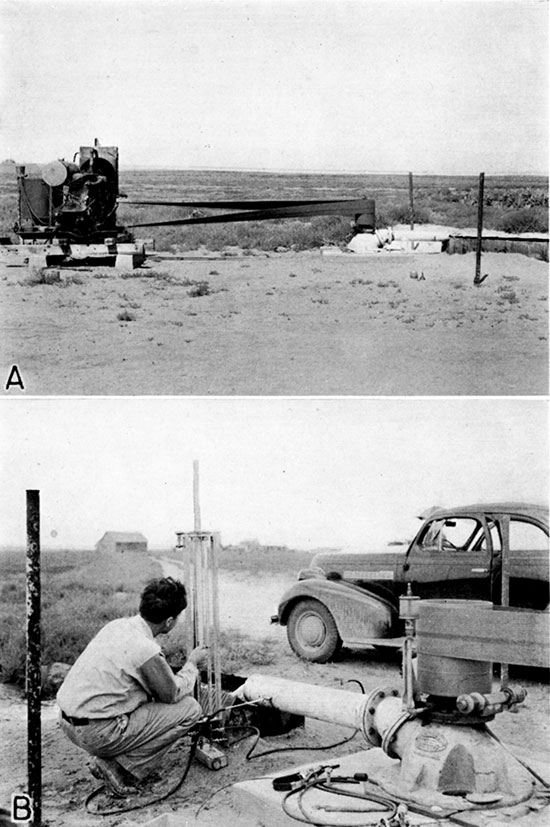

Of the 15 wells that were tested in Ford County, 8 are in the Arkansas valley, 4 are on the uplands south of the Arkansas valley, and 3 are in Crooked Creek valley in the southwestern part of the county. Most of the wells in the valley and all of the wells south of the Arkansas valley that were tested are single wells equipped with deepwell turbine pumps. Some, however, comprise a battery of wells connected to one pump, as noted in the table. Some of the pumps were operated by gasoline or distillate engines, and some were powered by electric motors. Measurements of the discharge were made in part by means of a Cipolletti weir (pls. 6B and 7B) and in part with a Collins flow gage (pl. 8B), which measures the velocity of the water in the discharge pipe of the pump. An electrical contact device was used for measuring the drawdowns in the wells while pumping and a steel tape was used for measuring the water levels when the pumps were not running.

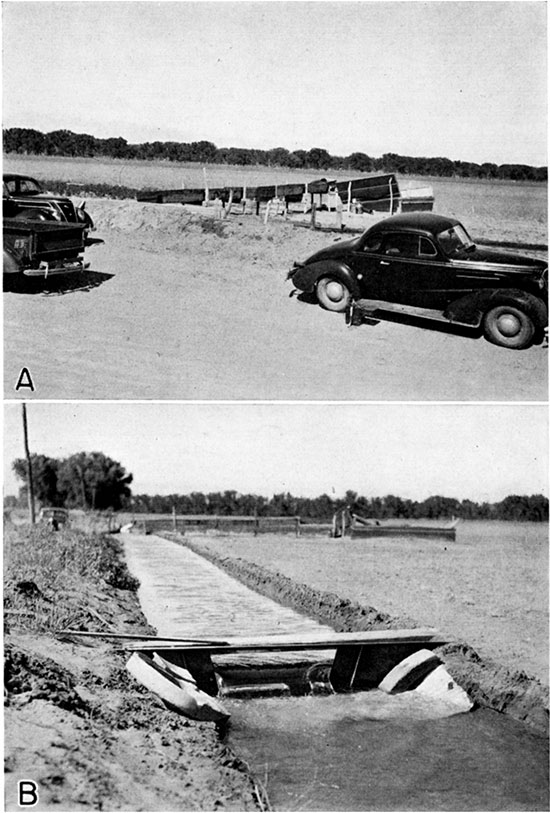

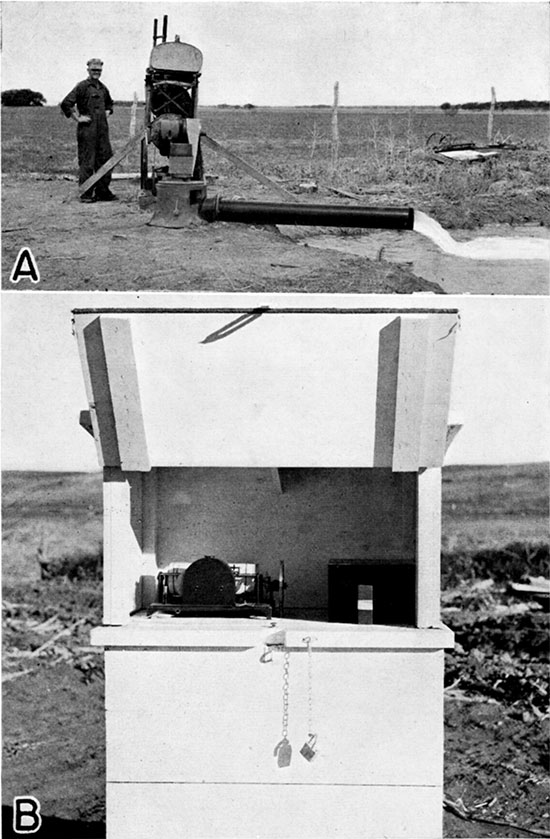

Plate 6--A, Irrigation well 320 in the Arkansas valley south of Howell. B, Discharge of well 320 being measured by Cipolletti weir during pumping test.

Plate 7--A, Typical deep-well turbine pump on well 417 in the Arkansas valley southeast of Ford. B, Discharge of 1,184 gallons a minute from well 417 flowing through Cipolletti weir during pumping test.

Plate 8--A, Typical upland irrigation well (403) equipped with a turbine pump driven by a combine engine. B, Measuring discharge of well 403 using a Collins flow gauge.

The pumping tests emphasized the fact that the irrigation wells in Ford County range widely in yield and overall efficiency. The yields of the 15 wells ranged from 320 to 1,200 gallons a minute and the specific capacities ranged from 13.1 to 204 gallons a minute per foot of drawdown. The drawdowns ranged from about 3.5 feet to more than 47 feet. There are many factors that determine the yield of wells, including the methods of construction, the character and thickness of the water-bearing formation, the diameter of the casing, the material used for casing, the quality of the water--whether harmless or corrosive or whether likely to form incrusting material readily, the type and placing of the screen, the development of the well, the finishing of the well--whether gravel-packed or not, the age of the well, and, for battery wells, the spacing of the wells. There are doubtless other factors, but the most important ones are listed. The relative importance of the different factors vary for different wells and under different conditions.

Construction of irrigation wells--Several methods have been used in constructing irrigation wells in Ford County. Some irrigation wells have been put down by professional drillers; others have been drilled by the owners. Almost all of the professional drilling has been done with cable-tool rigs, although one portable hydraulic rotary rig has been used extensively in the county for test drilling. Most of the small irrigation wells in the vicinity of Dodge City have been put down by the owners using homemade equipment.

The typical installation in the Arkansas valley, where the water table stands only a few feet below the land surface, consists of one or more drilled wells pumped by one centrifugal pump installed at the surface or, more generally, in a pit. The type of casing used ranges from the ordinary commercial type of galvanized iron, to homemade types consisting of almost anything at hand. The casing in most of the irrigation wells in Ford County ranges in diameter from 16 to 24 inches and is most commonly made of galvanized iron. Perhaps the most common type of improvised casing used in shallow irrigation wells is made from ordinary 55-gallon oil barrels. The barrels are converted into casing by first knocking out the heads and then lapping the cylinders together end to end. Used hot-water tanks have been used similarly as a substitute for galvanized-iron casing. The rims of tractor wheels stacked one above the other have been used for casing one or two wells. Homemade casing that has been perforated haphazardly obviously is not as satisfactory as a manufactured casing perforated uniformly. The number and size of perforations is extremely important because the yield and the life of the well are dependent largely on them.

Many irrigation wells are curbed with concrete rings manufactured locally. These rings range in diameter from 12 to 24 inches and are about 4 inches thick. They are assembled, a few rings at a time, as the well is being drilled. Each ring rests flatly on the ring next below, the alignment being maintained by vertical iron rods that pass through holes in the rings and act as guides. Water enters the well through spaces between the rings. There appears to be less danger of the openings in concrete screens becoming sealed off by incrusting materials than with common galvanized-iron casing with punched perforations. Some farmers in the eastern part of the county have constructed their own concrete rings and have devised a rather ingenious method of sinking them. A metal shoe shaped like an inverted funnel is first placed in the hole, and concrete rings are placed around the shoe, one above the other, on iron rods serving as guides. The bottom end of the funnel is larger in diameter than the outside of the concrete rings, and serves as a reamer in keeping the hole larger than the casing. As material is removed from the hole by a sand bucket the casing and funnel-shaped shoe follow down by gravity. Sometimes additional weight in the form of sand bags is applied at the surface to facilitate downward movement of the casing. Sand buckets and sand pumps of various types are used in the valley for sinking wells.

Where the water table is comparatively deep some wells are partly dug and partly drilled. Generally, a pit is first dug to the water table and a hole is then drilled in the bottom of the pit. The sides of the pit are cribbed with wood or surfaced with concrete. The pump is generally installed over the casing on the floor of the pit. Two types of wells are used for irrigation, depending upon the character of the water-bearing material-wells that are gravel-packed and wells that are not. The methods of construction are slightly different, although the same type of drilling equipment is used in both methods. In constructing a gravel-packed well, the hole is made somewhat larger than the casing and an outer "dummy" casing is generally used. The annular space between the outer blank casing and the inner screened or perforated casing is filled with screened gravel, and the outer casing is pulled up slowly as gravel-filling progresses. The functions and advantages of the gravel-packed well are described on pages 82, 83. The more common type of irrigation well in Ford County, however, is not gravel-packed, and is constructed by sinking a screened or perforated casing as the well is being drilled. The casing generally is weighted with sandbags and forced downward as the sand bucket removes the material. Individuals drilling their own wells generally erect tripods and use small gas engines for power. Well drillers use portable rigs, generally mounted on trucks. For a more detailed discussion of methods of constructing and developing wells, types of equipment used, gravel-walled wells, etc., the reader is referred to Davison (1939, pp. 10-23) and Rohwer (1940, pp. 18-40).

Some of the irrigation plants in the valley comprise two or more large wells connected to one pump and commonly called "battery wells." A battery of wells is used where the water table is comparatively shallow and where the thickness of the water-bearing formation is limited so that a single well of the same depth will not give the desired quantity of water. If the wells are spaced properly the yield from a battery of wells may be considerably greater than the yield from a single well, but the yield of each well is less than if the other wells were not being pumped. The typical installation consists of two or more wells, 40 to 50 feet apart, connected to one pump by a suction pipe laid in the ground just above the water table. The wells generally are put down in a straight line at right angles to the direction of movement of the groundwater. This type of plant has the advantage of having a flexible capacity--more wells can be added if production is less than desired. The yield does not increase proportionately with the addition of more wells, however, because of mutual interference between wells. For a more thorough discussion of battery wells and their construction and cost the reader is referred to Davison (1939, pp. 25-34) and Rohwer (1940, pp. 16-18).

Some irrigation wells in the valley are so constructed that they draw water from two distinct water-bearing beds--from the shallow alluvium and also from sands and gravels of the underlying Ogallala formation, at depths ranging from 100 to 150 feet. The presence of two separate water-bearing beds in the Arkansas valley has long been recognized, and the original city wells at Dodge City, drilled in 1906, tapped the so-called "second water" in order to obtain softer water. When wells were first drilled to the "second water" there was a popular belief that the efficiency of the wells would be increased if the upper water were cased off completely and only the "second water" were used. A well drawing water from the Ogallala formation alone yields softer water than a well that is supplied from both the alluvium and the Ogallala formation, but larger yields are obtainable from wells that tap both sources.

In 1939, there were 10 irrigation wells south of the Arkansas valley in Ford County. Three of these wells (507, 510, and 522) are situated in the valley of Crooked Creek--the others are on the uplands. The depth to water level in the upland wells ranges from about 86 to 135 feet, and the depths of all 10 wells ranges from 116 to 211.5 feet (table 15).

The wells on the south uplands were constructed by digging an open hole down to the water level and sinking a 16 to 20-inch casing down into the water-bearing formation. Well 485, a typical upland well (pl. 9A), is an open hole, 4 feet in diameter and about 130 feet deep, uncurbed except for a concrete wall to a depth of about 30 feet below the land surface. A 20-inch galvanized-iron casing has been sunk at the bottom of the 4-foot hole to a depth of 154 feet below land surface. The depth to water level is about 135 feet. Wells 402, 423, 425, and 435 were constructed in a similar manner. In constructing most of these wells, a hole was dug down to a depth where a sand bucket could be operated in the saturated water-bearing material, below which a 20-inch casing was sunk using a sand bucket.

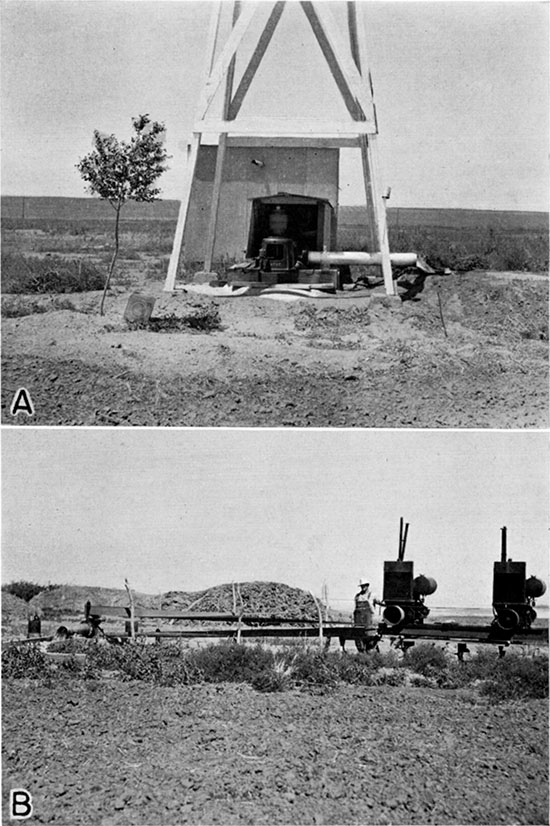

Plate 9--A, Typical upland irrigation well (485) equipped with turbine pump. B, Turbine pump on well 435, driven by two combine engines.

The three wells (507, 510, and 522) in the valley of Crooked Creek were drilled by a commercial driller and range in depth from 149 to 211.5 feet (see logs 78, 79, and 80). The depth to water level in these three wells range from 23 to 45 feet below land surface. The wells were drilled to a diameter of 30 inches, and equipped with perforated, oil-well casing 16 inches in diameter, surrounded by an envelope of screened gravel. Perforations one-fourth inch wide were cut in the blank casing with a torch and the sections of casing were welded together. Wells 507 and 510 are equipped with 60 feet of perforated casing and well 522 has 82 feet of perforated casing.

It is probable that irrigation wells of greater capacity and efficiency could be obtained in Ford County if better methods of well construction were employed. Some of the wells do not penetrate completely the water-bearing formation and would doubtless yield more water if deepened.

In some parts of the county the sediments comprising the water-bearing formation are so fine-textured that well screens should be gravel-packed in order to obtain satisfactory yields. In all but the eastern part of the Arkansas valley in Ford County, however, the materials comprising the alluvium generally are coarse enough that gravel-packing is not necessary, and very few wells have been constructed with gravel envelopes. Gravel packing should be recommended only after thorough test drilling has shown that the water-bearing material is so fine-textured that the water surrounding the screen cannot move readily into the well. The grade size of the material to be used in the gravel screen should be determined following an examination of the samples of material obtained from test drilling and after the dimensions of the perforations of the well screen have been decided upon. Because of the added construction costs involved, gravel-packing should be recommended only in eases where it is absolutely essential in order to obtain satisfactory yields.

In some of the wells the water level in the casing when the pump is running is several feet below the water level on the outside of the casing, so that the water spurts into the well through the open perforations, indicating that the material immediately surrounding the screen is too fine or has become clogged with fine sand preventing the water from moving in toward the well, or that the perforations are too small to admit water freely. By remedying one or both of these conditions the drawdown can be lessened and the yield of the well increased.

Depth and diameter of irrigation wells--The depth and diameter of irrigation wells are given in tables 9 and 10.

Table 9--Irrigation wells in Ford County classified according to depth.

| Depth (in feet) | Number of wells in the Arkansas valley |

Number of wells south of the Arkansas valley |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 10 | 2 | |

| 10-20 | 39 | |

| 20-30 | 68 | |

| 30-40 | 17 | |

| 40-50 | 7 | |

| 50-100 | 8 | |

| 100-150 | 5 | 5 |

| 150-200 | 7 | 4 |

| 200-211.5 | 0 | 1 |

| Totals | 187 | 10 |

Table 10--Irrigation wells in Ford County classified according to diameter.

| Diameter (in inches) |

Number of wells in the Arkansas valley |

Number of wells south of the Arkansas valley |

| 1 1/4 | 1 | |

| 2 | 1 | |

| 8 | 2 | |

| 10 | 9 | |

| 12 | 14 | |

| 14 | 12 | |

| 15 | 10 | |

| 16 | 51 | 6 |

| 18 | 3 | |

| 19 | 4 | 2 |

| 20 | (b) 44 | 2 |

| 22 | 12 | |

| 24 | 10 | |

| 34 | 1 | |

| 36 | 2 | |

| 42 | 1 | |

| 48 | 3 | |

| Unknown | 7 | |

| Totals | 187 | 10 |

|---|

a. For dug and drilled wells, diameter of drilled part is given

b. Includes one well in Edwards County

Most of the irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley in Ford County are 20 to 30 feet deep, many are only 10 to 20 feet deep, and only a few exceed 100 feet in depth. The depth of the 10 irrigation wells south of the Arkansas valley range from 116 to 211.5 feet.

The diameters of the irrigation wells range from 1 1/4 inches for the driven wells to 48 inches for the wells curbed with the rims of tractor wheels. Of the 187 irrigation wells visited in the Arkansas valley 124 are between 16 and 24 inches in diameter, of which the greatest number are 16 or 20 inches in diameter.

Types of pumps on irrigation wells--Most irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley in Ford County are equipped with centrifugal pumps, largely of the horizontal type, that range in size from 1 1/4 to 10 inches (table 11). Only 9 of the 187 wells visited were equipped with vertical centrifugal pumps. Eleven irrigation wells in the valley are equipped with turbine pumps. Two cylinder-type pumps were observed, but doubtless there are many other pumps of this type (most of which are probably powered by wind) used for small-scale irrigation on farmsteads.

Table 11--Types and sizes of pumps on irrigation wells in the Arkansas valley in Ford County.

| Type of Pump | Size (inches) | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Horizontal centrifugal | 1 1/4 | 1 |

| 1 1/2 | 2 | |

| 1 3/4 | 1 | |

| 2 | 19 | |

| 2 1/2 | 11 | |

| 3 | 48 | |

| 4 | 26 | |

| 5 | 14 | |

| 6 | (a) 29 | |

| 8 | 3 | |

| 10 | 3 | |

| Total | 157 | |

| Vertical centrifugal | 4 | 1 |

| 5 | 7 | |

| 6 | 1 | |

| Total | 9 | |

| Turbine | 8 | 2 |

| 12 | 1 | |

| 14 | 4 | |

| unknown | 4 | |

| Total | 11 | |

| Cylinder | 2 | 2 |

| None | 4 | |

| Removed | 4 | |

| Total | 10 | |

| Total number of pumps | 187 | |

The 10 irrigation wells south of the Arkansas valley are equipped with turbine pumps. The number of stages, or bowls, in each well range from 2 to 5 and the diameter of the bowls generally is about 14 inches.

The turbine is best adapted for pumping water from deep irrigation wells. The advantages of this type of pump are several--they are constructed so as to operate in relatively small diameter wells, no priming is necessary because the pump bowls are submerged, and the power unit is at the surface, thereby eliminating the need for a pump pit.

Type of power used for pumping irrigation wells--The type of power used to pump irrigation wells in Ford County is given in table 12. Gasoline engines are most commonly used for pumping from wells for irrigation in Ford County (pl. 10A). Most of the gasoline engines in use were removed from old combines. Many of these are belted to the pump pulley, and some are direct-connected to the pump shaft. Some pumps are powered by old car engines, some by stationary gasoline engines, several by tractor, and two by diesel engines. Fifty-five of the wells are operated by electric motors.

Plate 10--A, Irrigation well 248 equipped with turbine pump driven by combine engine. In the Arkansas valley 2 miles southwest of Dodge City. B, Automatic water-stage recorder on well 364 in the Arkansas valley about 1 mile southeast of Fort Dodge.

Table 12--Type of power used for pumping irrigation wells in Ford County.

| Type of Power | Number of wells in the Arkansas valley |

Number of wells south of the Arkansas valley |

|---|---|---|

| Gasoline engine | (a) 107 | 9 |

| Diesel engine | 2 | |

| Electric motor | 55 | |

| Tractor | 12 | 1 |

| None | 11 | |

| Totals | 187 | 10 |

| a. Includes one well in Edwards County | ||

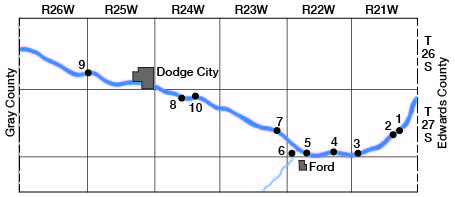

Irrigation water pumped from streams--Pumping water from streams for irrigation is practiced to a considerable extent in Ford County, principally along Arkansas River but to some extent along some of the smaller streams (pl. 11 B). In the Arkansas valley, there are 10 river pumping plants, the locations of which are shown in figure 19. All of these pump from Arkansas River, with the exception of plant 6, northwest of Ford, which pumps out of a small lake created by a dam across Mulberry Creek near its mouth. Plant 9 pumps out of an abandoned sand pit on the north bank of Arkansas River southeast of Sears siding. Plant 8 is situated just above the diversion dam across Arkansas River maintained by the Wilroads Rehabilitation Project (pl. 4). The water from this plant is used for irrigating some of the small tracts that cannot be reached by the gravity ditch. The total amount of irrigation water pumped from streams in the Arkansas valley is estimated to be about 734 acre-feet (table 13). Approximately 600 acres were irrigated in 1938 from these plants.

Plate 11--A, "Turtle back," a prominent feature on the south side of Sawlog creek in northern Ford County. The Dakota formation in the lower slope is overlain by the Graneros shale which in turn is capped by Tertiary Ogallala formation. B, Typical plant for pumping irrigation water from Sawlog creek, in northern Ford county. Situated about 200 yards above a dam across the creek in the SW cor. SE sec. 2, T. 25 S., R. 24 W.

Figure 19--Map of the Arkansas Valley in Ford County showing the locations of 10 river pumping plants.

Table 13--Acreage irrigated with water pumped from streams, and estimated pumpage in the Arkansas valley in Ford County in 1938.

| Pumping plant No., Fig. 19 |

Owner | Acres irrigated |

Total pumpage (acre-feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ray Shellheimer | 52 | 44 |

| 2 | M.E. Neal | 65 | 55 (a) |

| 3 | J.L. Riegel | 40 | 40 (a) |

| 4 | Wm. C. Fowler | 42 | 40 |

| 5 | G.R. Hensley | 42 | 20 |

| 6 | J.C. Lovette | 20 | 29 |

| 7 | J.E. Burke | 95 | 112 |

| 8 | Wilroads Gardens (Rehabilitation Project) |

100 (a) | 180 |

| 9 | Chas. Stapes | 60 (b) | 66 |

| 10 | Judge Karl Miller | 75 | 148 |

| Totals | 591 | 734 | |

| a. Approximately 300 acres are covered by water that flows by gravity from a diversion dam on the river and from a river pumping plant. The number of acres covered by the pump is indeterminate, therefore the figure given in the table is an estimate. | |||

There are several other pumping plants that draw water from Sawlog and Duck creeks in the northern part of the county for which acreage and pumpage figures are not available. In several places dams have been constructed across these streams and the water thus impounded is pumped to higher ground for irrigating feed crops. One such plant is situated on the bank of Sawlog creek about 200 yards upstream from the dam in the SW corner SE sec. 2, T. 25 S., R. 24 W.

Possibilities of Further Development of Irrigation Supplies from Wells

The ability of an underground reservoir to yield water over a long period of years is just as definitely limited as that of a surface-water reservoir. If water is withdrawn from an underground reservoir by pumping faster than water enters it, the supply will be depleted and water levels in wells will decline. The amount of water that can be withdrawn annually over a long period of years, without depletion of the available supply which may be termed the safe yield, is largely dependent upon the capacity of the underground reservoir and upon the amount of water that is added annually to the reservoir by infiltration in favorable recharge areas.

The feasibility of developing additional water supplies from wells for irrigation in Ford County is dependent not only upon the safe yield of the underground reservoir, but also upon other complex geologic, hydrologic, and economic factors. The depth to water level determines, in part, the depth of wells and the costs of drilling, of pumping equipment, and of operation. In general, the greater the pumping lift the greater the cost of lifting water to the surface. The permeability and thickness of materials also has a bearing on the depth and construction of wells. On the uplands, for example, a well at one locality may encounter thick beds of permeable gravel and yield an adequate supply of water for irrigation, whereas a well a short distance away at the same depth may encounter little or no gravel and yield but little water. The character of the water-bearing formation also determines the type of well screen and the size and type of perforations to be used.

For purposes of description, the areas in which are possibilities for additional water supplies from wells for irrigation have been classified as follows: the Arkansas valley, the uplands south of the Arkansas valley, the area in the northeastern part of the county that is underlain by the Dakota formation, and the shallow-water area in the vicinity of Crooked Creek in the southwestern part of the county.

Arkansas Valley--The capacity of the alluvium and the underlying Ogallala formation in the Arkansas valley in Ford County appears to be large enough to withstand much more pumping for irrigation, particularly in parts of the valley in which there is now little if any pumping. The water table in the valley generally is near the surface (pl. 2) so that pumping lifts are low. In all but the eastern part of the valley, water from two separate water-bearing formations is available to irrigation wells. Conditions for recharge, moreover, are more favorable in the Arkansas valley than in any other part of the county (pp. 70-72).

If the groundwater supply in an area such as the Arkansas valley in Ford County is extensively developed by drilling many wells and drawing heavily from them, the water levels in the wells may inevitably decline. The mere fact that there is a decline in the water levels during a period of development when the rate of withdrawal is increasing is not necessarily an indication of over-development as long as the decline is not so great as to indicate the approach of pumping lifts beyond the economic limit. In evaluating the prospects for the possible additional development of groundwater supplies in the Arkansas valley, the following question arises: What is the safe limit of pumping; that is, what quantity may be pumped perennially without overdraft?

A study of the relations of water levels in observation wells in the Arkansas valley to the amount of pumpage should furnish reliable information as to the safe yield of the underground reservoir. If the water levels in the wells remain virtually stationary during a considerable period of pumping it may be concluded that the rate of recharge has been about equal to the rate of discharge, including both natural discharge and withdrawals from wells. Regardless of the manner in which the water levels fluctuate from day to day, if at the end of any period they return approximately to the position they had at the beginning of the period, the record of pumpage furnishes a measure of the recharge during the same period minus the natural loss.

Thus, the water levels in 10 wells (98, 101, 184, 184A, 248, 256, 319, 322, 358, and 417) situated in the Arkansas valley showed net declines, during 1939, ranging from 0.2 foot to 1.70 feet and averaging 0.70 foot. In 1940, however, the water levels in 7 of the 10 wells rose by amounts ranging from 0.02 to 0.72 foot whereas the water levels in 3 wells (256, 248, 184A) declined by amounts ranging from 0.11 to 0.65 foot. The 3 wells in which the water levels declined during 1940 were pumped during the irrigation season and are situated in the most heavily pumped parts of the valley. Thus, the water levels in the 10 wells showed an average net rise of 0.06 foot during 1940.

The hydrographs shown in figure 8 indicate that there has been no persistent downward trend in the water levels in wells 11, 101, 184, 358, and 417 in the Arkansas valley during the period from October, 1938, to July, 1941. In general, the hydrographs show that during this period the fluctuations of the water table in the Arkansas valley are of a seasonal type, and that the major trend of the water levels has been about stationary or slightly upward. In response to the above-normal precipitation the water levels in most of the wells rose appreciably during the part of 1941 for which records were available at the time of publication.

Water-level observations in the Arkansas valley in Ford County were begun in October, 1938, at a time when the water table presumably was somewhat lower than normal as a result of several years of subnormal precipitation and increased pumpage from irrigation wells. As pointed out under the discussion of climate (p. 29), the precipitation at Dodge City has averaged 4.85 inches below normal for the 10-year period from 1930 through 1939--the longest consecutive period of subnormal precipitation in the 65-year record of the station. Precipitation at Dodge City in 1939 was 7.53 inches below normal--the ninth driest year of record. Thus during the 10-year period the water levels in the Arkansas valley declined partly as a result, of subnormal precipitation and partly as a result of increased pumpage. In 1940, the precipitation at Dodge City was 25.84 inches, or 5.30 inches above normal--almost twice the annual precipitation in 1939--and the water levels in most of the wells in the Arkansas valley showed a net rise during the year. The trends in water levels during the period of record indicates, therefore, that the pumpage has not exceeded the safe yield, but a longer record of water levels will be needed in order to evaluate the safe yield.

In 1938 about 10,170 acre-feet of water was pumped from wells in the Arkansas valley, of which about 4,760 acre-feet was used to irrigate about 2,800 acres of crops (tables 4, 5, 6 and 7). The water-level fluctuations during the period of record seem to indicate that this rate of pumping is not depleting the underground reservoir and that some additional pumping can be undertaken without exceeding the safe yield. If additional development takes place, however, care should be exercised in the spacing of the wells in order to prevent local overdevelopment.

Conditions appear to be especially favorable for additional pumping from wells in several different parts of the Arkansas valley in Ford County. One such area is situated on the south side of the river between Dodge City and Ford. There is some pumping from wells for irrigation on the south side of the river, just east of Dodge City, and there is opportunity for additional development farther east. Although the valley is limited south of the river by the belt of sandhills, there are many acres of flat bottom land that doubtless could be irrigated by pumping from wells, if care were exercised in selecting areas with the most favorable soils. In this part of the valley, yields up to 500 gallons a minute may be expected from shallow wells in the alluvium; and larger yields might be expected from deeper wells or from a battery of wells. Deep test drilling on this side of the river indicates that the basal part of the Ogallala formation contains a considerable thickness of coarse, unconsolidated gravel capable of transmitting water freely to wells (see log of test hole 8, p. 211). A single deep well of the proper construction should be capable of yielding up to 1,500 gallons a minute. In this part of the valley the water-bearing material in the Ogallala is coarse enough that the additional expense of installing a gravel pack probably is not warranted, but in other parts of the valley the gravels in the Ogallala may not be as favorable, and the use of a gravel pack might improve the yield of wells drilled into the Ogallala.

There are several areas on the south side of the river, west of Dodge City, where additional pumping from wells might prove successful, provided that the land is selected where the soils are not too sandy. Well 320, on the south side of the river south of Howell, is a good example of a successful battery of shallow wells in this part of the valley. At this plant the 5 wells have a combined yield of 1,200 gallons a minute (pl. 6A). Well 248 is a good example of a single deep well equipped with a turbine pump that taps the Ogallala formation in the valley southwest of Dodge City (pl. 10A). Preliminary test holes should provide the necessary information to determine whether a deep or shallow well should be constructed and whether the well should be gravel-packed or not.

On the north side of the river between Fort Dodge and Ford is another irrigable part of the valley that has not yet been developed to any great extent. This area is just east of the heavily-pumped district between Dodge City and Fort Dodge. In 1939, this part of the valley contained only a few scattered battery wells. The logs of two deep test holes drilled in the valley just east of Fort Dodge by the Soil Conservation Service (logs 53 and 57, pp. 232, 234) indicate that a single deep well equipped with a turbine should prove to be successful for irrigating from as much as 60 to 80 acres of land in this area.

Some additional pumping from wells for irrigation might prove successful in the valley on the north side of the river, extending from a point northeast of Ford to Edwards County. In this part of the valley, however, the Cretaceous bedrock underlies the valley at shallow depth, the Ogallala formation is entirely absent in most places, and the alluvium is very thin in many places near the river. The alluvium in this part of the valley is much finer-textured and is not as productive as in other parts of the valley. For this reason many test holes have had to be drilled before suitable localities for irrigation wells could be selected. Thus, it was necessary to drill 13 test holes before the location for well 95 was chosen, and more than 13 test holes were necessary before some of the other wells in the area were located. In 1939 there were six small irrigation wells (89, 93, 95, 96, 98, 99, 101, and 339), that ranged in depth from 26 to 45 feet, in this part of the valley. Six of the wells are equipped with vertical centrifugal pumps, manufactured locally by the Wetzel Brothers, and two of the wells are equipped with horizontal centrifugal pumps. The wells are capable of yields up to about 500 gallons a minute. There are undoubtedly possibilities for some additional development in this part of the valley, but the yields of individual wells are apt to be rather small owing to the limited thickness and the low permeability of the alluvium. The yields of irrigation wells doubtless could be improved by the use of suitable gravel packs. No battery wells are known in this area, but it is possible that, with careful location and construction, this type of well might prove successful. It is doubtful whether the Dakota formation, known to underlie this part of the valley at shallow depth, would yield sufficient, quantities of water for irrigation.

Uplands south of Arkansas River--Water in quantity sufficient for irrigation has been obtained in several places on the uplands south of Arkansas River in Ford County, and it seems likely that irrigation wells can be drilled at several other places in this part of the county. The practicability of irrigation in this part of the county depends upon the quantity of water available and upon whether the water can be pumped from a considerable depth at a low enough cost.

In many parts of the uplands south of the valley the depth to water level is more than 100 feet, and in some places it ranges in depth from 150 to 200 feet (pl. 2). The depth to water level in seven irrigation wells on the uplands (402, 403, 417, 423, 425, 435, and 485) ranges from about 81 to 135 feet and in four of them is more than 100 feet. The yields of these seven wells range from about 240 to about 765 gallons a minute. Four of the wells were tested in 1939 and found to yield less than 360 gallons a minute.

Owing to the conditions under which the Ogallala formation was deposited, individual beds of sand and gravel beneath the uplands are discontinuous and may grade laterally into finer materials such as silt or clay. Thus, a well at one locality may encounter thick beds of permeable gravel, whereas a well not far away may encounter little or no gravel. These differences in the character of the water-bearing formation beneath the uplands, together with differences in well construction and in operating lifts, are responsible for differences in yield.

In general, pumping from wells for irrigation on the uplands south of the Arkansas valley has not proven to be entirely successful. With the exception of the three wells in the Crooked Creek valley in the southwestern part of the county, which are described under a separate heading, only one well is producing water in sufficient quantity to make operation of the pumping plant practical, and two engines are necessary to insure a satisfactory yield from this well. Most of the well owners reported that pumping water from wells for irrigation in upland areas has not proved profitable in places where the total lifts are more than 100 feet and where the yields are relatively small. Several were of the opinion that the cost of pumping water under such conditions was in excess of any increase in production that resulted from the application of the water to the crops. In 1939 some of the well owners discontinued pumping operations after a short period of irrigation at the start of the growing season.

It is possible that with improved methods of constructing the wells the yields of wells on the uplands might be increased. Preliminary test holes should provide the necessary information in order to determine whether or not the well should be gravel-packed, and what type of screen to use. In some wells a natural gravel-pack can be, produced by careful development of the well by controlled pumping rates, immediately after completion of the well. In at least two of the upland plants upon which pumping tests were run the water levels immediately outside of the well screen during pumping were several feet higher than the water level inside the casing, indicating that the movement of water into the well was being impeded either by fine material surrounding the casing or by improper screen openings, or possibly both. This condition in one well was serious enough to cause the pump to hose suction and take air, with a resultant lowering of the yield when pumped beyond a certain rate. Proper construction doubtless would eliminate this trouble, reduce the amount of drawdown and consequently the total lift, and increase the yield. The depth to water level at any given locality will, undoubtedly be the most important factor in determining whether irrigation on the uplands can be economically successful.

Groundwater is pumped for irrigation at several other places on the uplands of the High Plains where conditions are somewhat comparable to those on the uplands of Ford County. In Scott County, Kansas, for example, approximately 17,160 acres were irrigated from wells in the Scott County shallow-water basin in 1940, according to a survey conducted by K.D. McCall of the Division of Water Resources, Kansas State Board of Agriculture, and the writer. Depths to water level in this area range from about 20 to 90 feet. At the end of 1940, there were approximately 90 irrigation wells in operation in Scott County. There are also several deep irrigation wells on the uplands in northern Finney and Kearny counties, Kansas, north and west of Garden City. The depths of the wells range from 200 to 300 feet and the depths to water level range from 40 to 70 feet.

Well 410 (table 15) on the uplands about half a mile north of Ensign, Gray County, is 200 feet deep, and the depth to water level in October, 1938, was about 165.3 feet. This well is reported to yield about 800 gallons a minute with an estimated drawdown of about 30 feet.

Schoff (1939, pp. 109-118) reported that there had been increasing interest on the part of farmers in Texas County, Oklahoma, in regard to the possibilities of irrigating from deep wells, and described four wells on the upland plains in Texas County. The wells range in depth from 238 to 298 feet, and the depths to water level range from 104 to 135 feet. The yields of these four wells range from about 425 to 960 gallons a minute with drawdowns ranging from 30 to 38 feet. All of them derive water from the Ogallala formation.

According to White, Broadhurst and Lang (1940, pp. 15-31), about 1,700 irrigation wells in the High Plains of Texas were pumped in 1939 and about 230,000 acres were irrigated from them. On the basis of a partly completed inventory it was estimated that about 400 wells were to be put down and equipped for irrigation in the Texas High Plains in 1940, representing a greater development than has taken place in any year except 1937. The development has reached proportions of considerable magnitude in more than 14 counties. The annual pumpage increased greatly during the period 1937-1939. In 1937 it amounted to about 130,000 acre-feet; in 1938, about 145,000 acre-feet; and in 1939, about 165,000 acre-feet. The depths of the wells range from 150 to 300 feet, and the depth to water level in the irrigated areas average about 60 or 65 feet. Most of the wells are equipped with turbine pumps capable of yielding from 500 to about 2,000 gallons a minute.

Northeastern shallow-water area--There is a large area covering almost the entire northeastern quarter of the county in which the depth to water level is less than 100 feet and in large parts of the area is less than 50 feet (pl. 2). Many of the wells in this part of the county obtain water from the Dakota formation, which underlies the area at shallow depth. The Ogallala formation rests on Cretaceous rocks ranging from the Greenhorn limestone to the Dakota formation and appears to be thin over much of the area. The sand and gravel deposits, so characteristic of the basal part of the Ogallala formation in other parts of the county, appear to be thin or absent over much of this area. In this area the Ogallala formation is composed largely of beds of caliche with a conspicuous absence of unconsolidated sand and gravel. Most of the beds are hard and cemented and consist largely of silty sand impregnated with calcium carbonate. The permeability of this material probably is low.

The sandstones of the Dakota formation underlying Ford County are fine-grained and do not yield water as freely as the Ogallala (p. 145), but under favorable conditions a well in the Dakota might yield as much as 250 gallons a minute. The possibilities of developing additional water supplies from wells for irrigation in the northeastern shallow-water area in Ford County are dependent largely on the water-yielding capacity of the Dakota formation. In parts of the area the Ogallala formation may furnish some water to wells, but it is probable that the yield would be too small for irrigation. The yields of wells in this area might be increased by drawing water from both sources. In order to furnish yields as high as 250 gallons a minute, wells in this area would have to be drilled to considerable depth into the Dakota formation. The depths of wells probably would average about 200 feet over much of this area. Although the depth to water level over much of the area is comparatively shallow, the specific capacities of wells penetrating the Dakota formation will be less than those of irrigation wells in other parts of the county, consequently the drawdowns will be greater.

If many irrigation wells are drilled into the Dakota formation in this area the wells should be spaced as far apart as possible because the effect of pumping is communicated more quickly and to greater distances in an artesian water-bearing formation, such as the Dakota formation, than it is under water-table conditions.

Southwestern shallow-water area--The shallow-water area along Crooked Creek in the southwestern part of the county is the northern extension of the Meade County artesian basin (p. 24). In an area covering approximately 22 square miles the depth to water level is less than 50 feet, and in much of the area in the vicinity of Crooked Creek the depth to water level ranges from about 4 to 25 feet (pl. 2).

Wells in this part of the county may encounter more than one water-bearing formation, and some of the wells penetrate as many as 3, including recent deposits of sand and gravel, the Ogallala formation and the Dakota formation. Most of the artesian water that supplies the flowing wells in the vicinity of Crooked Creek is derived from Pleistocene sands and gravels and from the Ogallala formation.

In 1939 there were three successful irrigation wells (507, 510 and 522) in this part of Ford County, and several others in adjacent areas in Meade County. The three wells in Ford County are of similar construction and range in depth from 149 to 211.5 feet. Sites for the wells were selected by drilling test holes by the hydraulic rotary method, and the most successful test hole was reamed out to a diameter of 30 inches by the same method. The wells have 16-inch perforated casings and are gravel-packed. The depths to water level range from about 23 to 45 feet. The saturated water-bearing material ranges in thickness from 52 feet in well 510 to 124 feet in well 507 (see logs of test holes 19, 20, and 21). The yields of these wells range from 570 to 950 gallons a minute.

Although relatively small in size, the southwestern shallow-water area has excellent possibilities for the development of additional irrigation water from wells. Water in sufficient quantity for irrigation can be obtained in any part of this area, and the pumping lifts are low.

Prev Page--Utilization || Next Page--Quality

Kansas Geological Survey, Ford County Geohydrology

Web version April 2002. Original publication date Dec. 1942.

Comments to webadmin@kgs.ku.edu

The URL for this page is http://www.kgs.ku.edu/General/Geology/Ford/05_gw7.html